SCRP 2009

My research

examines the pollination biology and population genetics of Joshua trees (Yucca

brevifolia). If

you’re not familiar with Joshua trees, they are large, woody monocots (the group

of plants that includes grasses, orchids, and palm trees) that are endemic to

the Mojave Desert region of California, Arizona and Nevada. Joshua trees are

known for their comical (or ugly, depending on your outlook) appearance, and

for their remarkable pollination biology (see below). John C. Fremont, an early

American explorer described them as “The most repulsive tree in the vegetable

Kingdom”. Later, Mormon settlers saw in their silhouette the figure of the

prophet Joshua, pointing the way to the Promised Land.

Students

working in my lab will work on projects related to one of two aspects of the

biology of Joshua trees. One project, which is currently fairly well developed,

looks at the pollination biology of these remarkable plants. The second project,

which is still in early stages of development, looks at the effects of global

warming on population growth rates. Below, I’ve provided detailed information

about these two projects, along with relevant references and citations, and

some ideas for questions that could be answered in student projects. Students

interested in applying to work in my lab should read the project descriptions

below, and the descriptions of potential student projects.

When

submitting their SCRP application, students should explain in a 3-5 page

essay (as described

on the SCRP

webpage) their ideas for how they might answer some of questions

identified in the project description (below). This essay should do two things:

1. It should present a coherent plan for how student research could address the

question, and 2. It should show that the applicant has done background reading

and research.

Background reading could include reading some of the references listed here,

but should also include other relevant research articles from the primary

literature. These articles might be examples of how other scientists have

tackled similar problems, or general articles about the natural history of the

system, or the theory behind the statistics and experimental design. Of course,

it will be challenging to put together a clear research proposal for a system

that students have only recently read about. The main things that I will be

looking for in reviewing student application are the ability to think clearly

about the problems, and that the applicants have taken some initiative to learn

about the systems and relevant concepts. I also encourage prospective SCRP

students to meet with me before submitting their application to discuss their

ideas.

Joshua Tree Pollination Biology

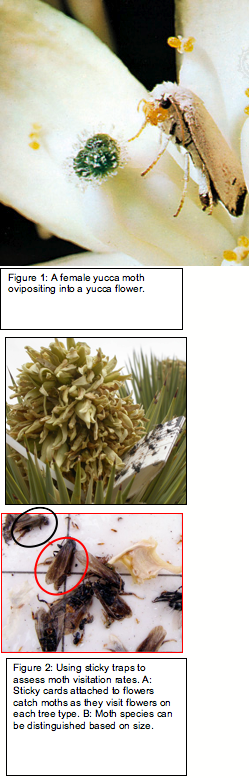

Joshua

trees (Yucca brevifolia), like all yuccas, are pollinated exclusively by highly specialized

yucca moths. The moths, in turn, lay their eggs exclusively on the flowers of

the Joshua tree, and as the flower develops into a ripening fruit, the moth’s

larvae feed on the developing seeds. To ensure that the flower will develop and

provide food for her offspring, the female yucca moth deliberately deposits a

load of pollen directly onto the flower’s stigmatic surface using specialized,

uniquely derived, tentacle-like mouthparts (Pellmyr 2003). The interaction between yuccas and

yucca moths is therefore the archetypical example of an obligate pollination

mutualism, one which Darwin called “the most remarkable pollination system ever

described” (Darwin 1874).

Within this

system, there is thought to be strong reciprocal natural selection

(coevolution) promoting phenotype matching between Joshua trees and their

pollinators. Across species, there is a strong, statistically significant

correlation between the length of the female moth’s ovipositor (a blade-like

appendage used to cut into flowers when laying eggs) and the thickness of the

flower’s ovary wall at the site of oviposition. Likewise, there are strong

functional constraints acting on both moth and pollinator features: the moth’s

ovipositor must be long enough to reach ovules within the flower, but an

ovipositor that is too long may injure the developing flower, which can prompt

flower to die along with the moth’s larvae (Marr and Pellmyr 2003). (See Figure 1)

In the

Joshua tree system specifically, recent work revealed that across its range Y.

brevifolia is

pollinated by two distinct, parapatrically distributed moths, Tegeticula

synthetica Riley in

the west, and T. antithetica Pellmyr in the east (Pellmyr and Segraves 2003). These two moths differ

significantly in overall body size, and in the size of the female ovipositor (Pellmyr and Segraves 2003). Recent work has shown that Joshua

trees pollinated by the different moth species differ significantly in overall

floral and vegetative morphology, and differ more than any other feature in the

length of the floral stylar canal – the path through which the female

yucca moth inserts her ovipositor during oviposition (Godsoe et al. 2008). These patterns suggest that floral

style length and moth ovipositor length may experience reciprocal natural

selection (coevolution in the strict sense) favoring phenotype matching.

One way to

test his hypothesis would be to compare the performance of moths of a given

ovipositor length on flowers that differ in style length using a reciprocal

transplant experiment, but to do so would require moving moths between different

populations, keeping the moths alive during transport, and forcing them to

interact with foreign trees. These factors potentially make testing this

hypothesis very challenging. However, the recent discovery of a ~4 km-wide

contact zone where the two species of yucca moth co-occur in Tikaboo Valley,

Nevada (Smith et al. 2008) now makes it possible to address

this question using a ‘natural experiment’. Contact zones like that in Tikaboo

Valley have been used in other pollination systems to study the role of natural

selection and host preference in maintaining species boundaries (Fulton and Hodges 1999; Grant 1952;

Hodges and Arnold 1994), but such an approach has not

previously been used in an obligate pollination mutualism.

Within

Tikaboo Valley, trees with different pollinator-associated morphotypes occur side-by-side,

along with some trees that appear to be intermediate between the two types, and

there is greater variation in both style length and ovipositor length than in

any other population. Although moths of both species have been collected on

each of the tree morphotypes in the zone of sympatry, it is unclear whether

female moths show a preference in oviposition for trees whose floral morphology

matches their ovipositor. If reciprocal natural selection favors phenotype

matching in this system, then moths ovipositing on the “wrong” tree type should

have reduced fitness in terms of offspring that survive to adulthood.

We can

begin to address some of the questions by measuring how often moths move

between the two tree types in the contact zone, and how often the moths

successfully lay eggs on each of the two trees. By attaching plastic cards

coated in glue to receptive flowers we can trap moths as they visit the trees,

and then determine how often each species visit the different tree types. (See

Figure 2). Likewise, we can get a rough idea about how often the two moths oviposit

into the “wrong flowers” by collecting larvae as they emerge from fruits.

Although the larvae of the two species are essentially indistinguishable in

appearance, we can compare mitochondrial DNA, as well as regions of highly

variable DNA called microsatellites, to identify the larvae to species.

My

colleagues at the University of Idaho and I completed an experiment like this

in 2007, with the following results:

|

A. Moth visitation rates |

|

||

|

|

Moth species (forewing length) |

|

|

|

Tree Type |

T. antithetica |

T. synthetica |

∑ |

|

Eastern |

10 |

3 |

13 |

|

Western |

22 |

23 |

45 |

|

∑ |

32 |

26 |

58 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

B. Larval emergence rates |

|

|

|

|

|

Larval mitotype |

|

|

|

Tree Type |

T. antithetica |

T. synthetica |

∑ |

|

Eastern |

296 |

3 |

299 |

|

Western |

15 |

45 |

60 |

|

∑ |

311 |

48 |

359 |

Table 1: Estimates of host specificity and

oviposition success of each moth species on each tree type. Intermediate

(hybrid) trees were not included in this experiment. Visitation rates are based

on passive sampling using sticky-cards. Larval emergence rates reflect larvae

collected from fruits of each tree type, identified to species using mtDNA

sequencing.

Whereas eastern trees are visited primarily by T.

antithetica (the eastern moth), western trees

receive almost exactly equal visitation by the two moth species. A similar

asymmetry is seen in the larvae emerging from the two tree types. Whereas 99%

of the larvae emerging from eastern trees are of the eastern moth species (T.

antithetica), a

full quarter of the larvae on western trees are of the eastern moth species.

These preliminary results suggest that western moths (T. synthetica) are either much more ‘choosy’

about which trees they will visit, or have a much more difficult time laying

eggs when they visit their non-native tree (or possibly both). However, we

still don’t know exactly what mediates host specificity and ovipositon success

in this system, so there are still a lot of questions we would like to answer. Many

of these could be the subjects of student research projects.

1.

Currently,

we differentiate between the two moth species caught in the sticky traps based

on the size of the insects forewings. However, the moths definitely vary in

body size within species, so it’s possible that we are sometimes mistaking an

individual of one species, for an individual of the other. It would therefore be desirable to know how

reliable body size is in telling the two moth species apart. Is there a way

that we could ‘double check’ species identifications?

2.

We are

currently using DNA sequencing to distinguish larvae of the two moth species

that emerge from fruits. There are some drawbacks to this, however. DNA

sequencing is very expensive, and takes a lot of time. We would like to develop

a less expensive way to distinguish larvae. One way would be to see if there

are reliable morphological differences that could allow us to tell the two

species apart at the larval stage. Another approach would be to use some less

expensive means of genotyping the larvae. Some possibilities include using

microsatellite DNA, or methods such as ‘PCR RFLP’s’, or regular old RFLP’s to

distinguish larvae.

3.

As I

mentioned above, at the Tikaboo valley site, there are not only “western” and

“eastern” trees, but also some trees that are morphologically intermediate, that

might be hybrids. We’d like to know how often the moths of each species visit

these hybrid trees. If it really is matching between the flower’s style and the

moth’s ovipositor that makes a difference, you would expect the western moths

to do a little bit better on flowers with medium-sized styles.

4.

Obviously,

one key step in the experiment above is being able to reliably distinguish

between “eastern” and “western” trees in the hybrid zone. So, it would be

desirable to develop quantitative measures of how reliable different features

are for distinguishing different tree types (see the Godsoe et al paper for

details about different morphological features), and how often morphological

measures of tree type agree with genetic measures.

5.

Lastly,

we’d like to know whether the geographic location of trees within the contact

zone affects how many moths of each species visit the trees. The contact zone

is fairly small (about 4 KM across), and on either side of the contact zone are

populations of “pure” eastern or western trees. You might expect that trees

that are closer to –say- the western edge of the contact zone would

receive more western moths, and this could mess up our estimates of host

specificity. How could we test this hypothesis?

Consequences of Global Warming

for Joshua Tree

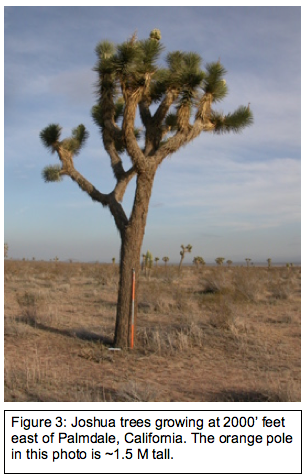

Based on

the environments where Joshua trees currently grow, we can use climate data to

infer the range of environments that they are theoretically able to occupy (their

fundamental niche). By then combining these “niche models” with predictions of

the climate is expected to change over the next century, we can develop

predictions about how the Joshua tree may respond to global warming. Based on

these models, Joshua tree is predicted to be severely impacted by global

warming over the next century (Dole et al. 2003; Shafer et al.

2001); local population extinctions are

projected over much of its current range. Populations at low elevations, and in

the southern portion of the range, including much of Joshua Tree National Park

and the Mojave National Preserve are expected to go extinct.

The time scale

on which these extinctions may occur is unclear, however. If we compare

populations in areas expected to experience local extinctions, with those that

are predicted to retain Joshua trees, there is a striking difference in the

character of the populations. In areas expected to experience population

declines and extinctions, population density is extremely low, and most trees

are very large and (apparently) very old. (See Figure 3). Conversely,

populations at higher elevations are composed primarily of young,

pre-reproductive trees (See Figure 4). This pattern is even more noticeable if

we compare the proportion of the population in different “size classes” (Table

2).

|

Size Class |

% of Population |

|

|

|

4000’ |

2000’ |

|

Seedlings |

75 |

35 |

|

2 |

8 |

3 |

|

3 |

6 |

12 |

|

4 |

7 |

16 |

|

5 |

3 |

15 |

|

6 |

1 |

11 |

|

7 |

0 |

5 |

|

Oldest |

0 |

4 |

Table 2:

Size class data for Joshua trees near Palmdale, CA.

At the high

elevation site in Table 2, almost all of the trees are in the smallest size

class, and only a small minority of trees is beyond the seedling stage. On the

other hand, at the low elevation site, the majority of trees are past the

seedling stage, and many are very old indeed. These differences in demography

are typical of what we see in human populations experiencing either population

growth (majority or the population is in the youngest age class), or population

decline (majority of the population in older age classes) (Gotelli 2001).

If populations in the warmest

climates are already on their way to extinction, it suggests that the effects

of climate change may be much more dire for Joshua tree than the current models

would predict. The underlying models assume that every place that Joshua tree

currently exists represents an area where the trees can flourish. However, if

many of these areas are actually not suitable, because the current climate is

actually too warm or too dry, the future range of Joshua tree may be even

smaller than we currently expect.

This project is still in its infancy,

however, so there are lots of questions we’d like to know the answer to.

1. The data presented here represent a

comparison across an elevational gradient in one part of the range. Would we

find similar patterns in other parts of the range?

2. The data here are based on size

classes. However, size classes are not really a very good way to estimate demography.

Just for one thing, maybe trees actually grow at different rates in different

elevations or different climates. So, we’d like to develop some independent

estimate of tree age. We can’t use tree rings, because Joshua trees are

monocots, and don’t have tree rings. One approach that has been useful for

other plants that lack tree rings is to use radiocarbon dating to estimate the

age of trees (Vieira et al. 2005). Could such an approach be used

here?

3. Could the differences in size class

data be used to estimate the rates of population growth and decline in

different populations? What kind of additional information would we need?

4. Another common approach to studying

population growth and population expansion is to use genetic data, such as

microsatellites, to try to measure growth rates (Cornuet and Luikart 1996). Would such an approach be possible

here?

Some Useful References:

Cornuet, J. M., and G. Luikart. 1996. Description and Power

Analysis of Two Tests for Detecting Recent Population Bottlenecks From Allele

Frequency Data. Genetics 144:2001-2014.

Darwin, C. 1874. Letter to J D

Hooker, April 7, 1874 in F. Burkhardt, and S. Smith, eds. A Calendar of the Correspondence of

Charles Darwin, 1821-1882 Cambridge, The Press Syndicate of the University of

Cambridge.

Dole, K. P., M. E. Loik, and L. C.

Sloan. 2003. The relative importance of climate change and the physiological

effects of CO2 on freezing tolerance for the future distribution of Yucca

brevifolia. Global and Planetary Change 36:137-146.

Fulton, M., and S. A. Hodges. 1999.

Floral isolation between Aquilegia formosa and Aquilegia pubescens. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B 266:2247-2252.

Godsoe, W. K. W., J. B. Yoder, C. I.

Smith, and O. Pellmyr. 2008. Coevolution and divergence in the Joshua

tree/yucca moth mutualism. American Naturalist 171:816-823.

Gotelli, N. J. 2001, A Primer of

Ecology. Sunderland, MA, Sinauer.

Grant, V. 1952. Isolation and

hybridization between Aquilegia formosa and A. pubescens. Aliso 2:341-360.

Hodges, S. A., and M. L. Arnold.

1994. Floral and ecological isolation between Aquilegia formosa and Aquilegia pubescens. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences 91:2493-2496.

Marr, D. L., and O. Pellmyr. 2003.

Effect of pollinator-inflicted ovule damage on floral abscission in the

yucca-yucca moth mutualism: the

role of mechanical and chemical factors. Oecologia 136:236-243.

Pellmyr, O. 2003. Yuccas, yucca

moths and coevolution: a review. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden

90:35-55.

Pellmyr, O., and K. A. Segraves.

2003. Pollinator divergence within an obligate mutualism: two yucca moth

species (Lepidoptera; Prodoxidae: Tegeticula) on the Joshua Tree (Yucca

brevifolia;

Agavaceae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 96:716-722.

Shafer, S. L., P. Bartlein, and R.

S. Thompson. 2001. Potential changes in the distribution of western North

American tree and shrub taxa under future climate scenarios. Ecosystems

4:200-215.

Smith, C. I., W. K. W. Godsoe, S.

Tank, J. B. Yoder, and O. Pellmyr. 2008. Distinguishing coevolution from

covicariance in an obligate pollination mutualism: Asynchronous divergence in

Joshua tree and its pollinators. Evolution 62:2676-2687.

Vieira, S., S. Trumbore, P. B.

Camargo, D. Selhorst, J. Q. Chambers, N. Higuchi, and L. A. Martinelli. 2005.

Slow growth rates of Amazonian trees: Consequences for carbon cycling.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

102:18502-18507.