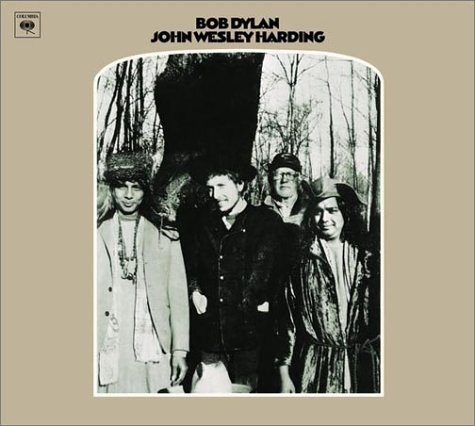

Eighth Recording: John Wesley Harding

Recorded October-November 1967, Nashville Studios

Released December 1967

Lyrics

Interviewer: The Buddhist tradition talks about illusion, the Jewish tradition about allusion. Which do you feel closer to?

Dylan: I believe in both, but I probably lean to allusion. I'm not a Buddhist. I believe in life, but not this life.

Interviewer: What life do you believe in?

Dylan: Real life.

Interviewer: Do you ever experience real life?

Dylan: I experience it all the time, it's beyond this life.

*********

Interviewer: There's a lot of talk about magic in Streel-Legal. "I wish I was a magician/I would wave a wand and tie back the bond/That we've both gone beyond" in "We Better Talk This Over,""But the magician is quicker and his game /Is much thicker than blood" in "No Time to Think."

Dylan: These are things I'm really interested in, and it's taken me a while to get back to it. Right through the time of Blonde on Blonde I was doing it unconsciously. Then one day I was half-stepping, and the lights went out. And since that point, I more or less had amnesia. Now, you can take that statementas literally or metaphysically as you need to, but that's what happened to me. It took me a long time to get to do consciously what I used to be able to do unconsciously.

John Wesley Harding was a fearful album -- just dealing with fear [laughing], but dealing with the devil in a fearful way, almost. All I wanted to do was to get the words right. It was courageous to do it because I could have not done it, too. Anyway, on Nashville Skyline you had to read between the lines. I was trying to grasp something that would lead me on to where I thought I should be, and it didn't go nowhere -- it just went down, down, down. I couldn't be anybody but myself, and at that point I didn't know it or want to know it.

I was convinced I wasn't going to do anything else, and I had the good fortune to meet a man in New York City who taught me how to see. He put my mind and my hand and my eye together in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt. And I didn't know how to pull it off. I wasn't sure it could be done in songs because I'd never written a song like that. But when I started doing it, the first album I made was Blood on the Tracks. Everybody agrees that that was pretty different, and what's different about it is that there's a code in the lyrics and also there's no sense of time. There's no respect for it: you've got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there's very little that you can't imagine not happening.

--Bob Dylan (Jonathan Cott Interview, 1978)

Track listing

The track durations cited here are those of the remastered version released September 16, 2003 and re-released June 1, 2004. Previous versions differ

Lyrics

Side One

1. "John Wesley Harding" – 2:58

2. "As I Went Out One Morning" – 2:49

3. "I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine" – 3:53

4. "All Along the Watchtower" – 2:31

5. "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest" – 5:35

6. "Drifter's Escape" – 2:52

Side Two

1. "Dear Landlord" – 3:16

2. "I Am a Lonesome Hobo" – 3:19

3. "I Pity the Poor Immigrant" – 4:12

4. "The Wicked Messenger" – 2:02

5. "Down Along the Cove" – 2:23

6. "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight" – 2:34

Personnel

* Bob Dylan - Guitar, Harmonica, Piano, Keyboards, Vocals

* Pete Drake - Steel Guitar

* Charlie McCoy - Bass

* Kenneth A. Buttrey - Drums

* Bob Johnston - Producer

* Charlie Bragg - Engineer

Liner Notes

from: http://www.bobdylan.com/moderntimes/linernotes/jwh.html

There were three kings and a jolly three too. The first one had a broken nose, the second, a broken arm and the third was broke. "Faith is the key!" said the first king. "No, froth is the key!" said the second. "You're both wrong," said the third, "the key is Frank!"

It was late in the evening and Frank was sweeping up, preparing the meat and dishing himself out when there came a knock upon the door. "Who is it?" he mused. "It's us, Frank," said the three kings in unison, "and we'd like to have a word with you!" Frank opened the door and the three kings crawled in.

Terry Shute was in the midst of prying open a hairdresser when Frank's wife came in and caught him. "They're here!" she gasped. Terry dropped his drawer and rubbed the eye. "What do they appear to be like?" "One's got a broken vessel and that's the truth, the other two I'm not so sure about." "Fine, thank you, that'll be all." "Good" she turned and puffed. Terry tightened his belt and in an afterthought, stated: "Wait!" "Yes?" "How many of them would you say there were?" Vera smiled, she tapped her toe three times. Terry watched her foot closely. "Three?" he asked, hesitating. Vera nodded.

"Get up off my floor!" shouted Frank. The second king, who was first to rise, mumbled, "Where's the better half, Frank?" Frank, who was in no mood for jokes, took it lightly, replied, "She's in the back of the house, flaming it up with an arrogant man, now come on, out with it, what's on our minds today?" Nobody answered.

Terry Shute then entered the room with a bang, looking the three kings over and fondling his mop. Getting down to the source of things, he proudly boasted: "There is a creeping consumption in the land. It begins with these three fellas and it travels outward. Never in my life have I seen such a motley crew. They ask nothing and they receive nothing. Forgiveness is not in them. The wilderness is rotten all over their foreheads. They scorn the widow and abuse the child but I am afraid that they shall not prevail over the young man's destiny, not even them!" Frank turned with a blast, "Get out of here, you ragged man! Come ye no more!" Terry left the room willingly.

"What seems to be the problem?" Frank turned back to the three kings who were astonished. The first king cleared his throat. His shoes were too big and his crown was wet and lopsided but nevertheless, he began to speak in the most meaningful way, "Frank," he began, "Mr. Dylan has come out with a new record. This record of course features none but his own songs and we understand that you're the key." "That's right," said Frank, "I am." "Well then," said the king in a bit of excitement, "could you please open it up for us?" Frank, who all this time had been reclining with his eyes closed, suddenly opened them both up as wide as a tiger. "And just how far would you like to go in?" he asked and the three kings all looked at each other. "Not too far but just far enough so's we can say that we've been there," said the first chief. "All right," said Frank, "I'll see what I can do," and he commenced to doing it. First of all, he sat down and crossed his legs, then he sprung up, ripped off his shirt and began waving it in the air. A lightbulb fell from one of his pockets and he stamped it out with his foot. Then he took a deep breath, moaned and punched his fist through the plate-glass window. Settling back in his chair, he pulled out a knife, "Far enough?" he asked. "Yeah, sure, Frank," said the second king. The third king just shook his head and said he didn't know. The first king remained silent. The door opened and Vera stepped in. "Terry Shute will be leaving us soon and he desires to know if you kings got any gifts you wanna lay on him." Nobody answered.

It was just before the break of day and the three kings were tumbling along the road. The first one's nose had been mysteriously fixed, the second one's arm had healed and the third one was rich. All three of them were blowing horns. "I've never been so happy in all my life!" sang the one with all the money.

"Oh mighty thing!" said Vera to Frank, "Why didn't you just tell them you were a moderate man and leave it at that instead of goosing yourself all over the room?" "Patience, Vera," said Frank. Terry Shute, who was sitting over by the curtain cleaning an ax, climbed to his feet, walked over to Vera's husband and placed his hand on his shoulder. "Yuh didn't hurt yer hand, didja Frank?" Frank just sat there watching the workmen replace the window. "I don't believe so," he said.

Bob Dylan -- Vocal, Guitar, Harmonica and Piano

Charles McCoy -- Bass

Kenny Buttrey -- Drums

Pete Drake -- Steel Guitar on "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight" and "Down Along The Cove"

Engineering -- Charlie Bragg

Produced by Bob Johnston

Some Reviews:

Bob Dylan, John Wesley Harding (Columbia)

US release date: 27 December 1967

http://www.popmatters.com/pm/review/dylanbob-john

by Nicholas Taylor

John Wesley Harding: The Apocalypse and the Sweet Morning After

Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding is an album of half-spoken secrets, hushed whispers, illegible writings, and missing pages. It is grainy black and white. It has the feel of antiquity settled on it like decades upon decades of quietly accumulating dust. It is beautifully anachronistic and elusive. It is hard, gritty, seemingly impenetrable. It is blindingly complex; addictively rewarding. All this is to say that it is classic Bob Dylan.

Dylan vacated his post as voice of a generation when he crashed his motorcycle in 1966, retreating up to Woodstock, New York to recuperate. After months of quiet country life spent reading the Bible and recording the wonderfully intimate sessions with the Band that were to become The Basement Tapes, in late 1967 Dylan was ready to return to the world of rock music. Sort of. He went down to Nashville and, backed by a group of local session players, cut the album that exposed the great divide that had grown between Dylan, the folkie, hipster, electric guitar playing Judas, and the Hippie generation that he had helped to create. He has traded in his shades for bifocals; his wild mane of tossled brown hair is now neat and shorn; his hip defiant Beat demeanor has been replaced by a wiser, older, bearded persona; in short, as Dylan had done many times before and would do many times again, he had reinvented himself.

Dylan’s new music was coarse and brittle. The setup was sparse—Kenny Buttrey’s dry, crackling drums, Charles McCoy’s thumping bass, and Dylan’s grating harmonica and occasional piano. Bob Johnston’s production was even sparser. Dylan and his band sound as if they are playing in a vacuum. The album is incredibly still. The songs are stark morality tales in an economical, simple language straight out of Ecclesiastes or Proverbs. The scene is a stark field-in the distance brews the apocalypse. This is amazingly heavy stuff when compared to his previous studio album, 1966’s /Blonde on Blonde/, a record of exuberant, hazy, ethereal, fluidly electric sounds, swimming in the blues, in acid, in smoke, in shadows.

The Book of Revelation looms large on John Wesley Harding. The album’s best-know track, “All along the Watchtower” (of Jimi Hendrix fame) begins with the ominous rationalization, “There must be someway out of here,” but there is no way out of here. The album is fated. The doom is inevitable. Dylan envisions the destruction in myriad forms and contexts. In “All along the Watchtower” the apocalypse is understated and foreboding: “Outside in the distance a wildcat did growl / Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl.” In “Drifter’s Escape,” a grooving morality tale, the coming end is more literal: as the drifter is condemned by the judge and the “cursed jury” (’cursed’ pronounced in that great archaic way, /kurr-sed/), a bolt of lightening strikes the courthouse “out of shape” as the crowd outside kneels and prays.

One of the strengths of this album, however, is that even something as dire as the wrath of a vengeful god is approached in both a somber and a comic light. These dark portraits of the apocalypse are contrasted by the wonderful pieces of black humor “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest” and “The Wicked Messenger”. In the former, a long, wieldy number reminiscent of the Woody Guthrie-inspired talking blues of Dylan’s early albums, “Eternity” is conceived of as the ultimate dream/nightmare of the lustful seeker: a “big house as bright as any sun / With four and twenty windows/ And a woman’s face in ev’ry one” in which Frankie, after an amorous rampage, dies of thirst. In the latter, the wicked messenger foretells the end of the world, only to be met with this mock serious retort from the angry, doomed crowd: “If ye cannot bring good news, then don’t bring any!” In Dylan’s vast, complex imagination, the coming doom can take on all these different forms-the result is a sense of fated destruction that is both harrowing and slightly ironic. It is unclear whether Dylan is saying the coming end is a bad thing or not.

Following the lead of the more somber side of his nightmare vision, on side two Dylan attempts to cope with the evil approaching through good old Christian morality. “Dear Landlord”, “I Am a Lonesome Hobo”, and “I Pity the Poor Immigrant” are all odes to the downtrodden, the weary, the dispossessed-in effect, they revisit the have-nots Dylan eulogized and celebrated on such early albums as /Bob Dylan/, /The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan/, and /The Times They Are A-Changin/. These intimate, simple songs are exhortations to compassion. Whereas the Old Testament dominated much of the first side, these lyrics are taken straight from the Sermon on the Mount. “And anyone can fill his life up with things,” sings Dylan on “Dear Landlord”, “he can see but he just cannot touch.” While Dylan was not overtly religious at this point in his life, he certainly was quite the moralizer. If the doom prophesied in “All along the Watchtower” was to be avoided, it had to be through a Christian sense of spiritual contentment and fellowship with one’s fellow human being. These tracks are achingly archaic and quaint because their Puritan message is archaic and quaint-the apocalypse can be avoided by small individual actions and feelings, as Dylan affirms in “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest”, “So when you see your neighbor carryin’ somethin’ / Help him with his load / And don’t go mistaking paradise / For that home across the road.”

There is an added layer to /John Wesley Harding/ that makes it infinitely rich and rewarding. Even this Puritanical path to salvation is subverted and put into question by the albums final tracks, “Down along the Cove” and “I’ll be Your Baby, Tonight”. The name of the game here is not compassion or grace or brotherhood among men-it is love. Love, not in the Christian way, but in the fifties pop song kind of way. You and your baby on a Saturday night, yeah yeah yeah. They stick out like sore thumbs because of their warmth of feeling and up front emotional directness. “Down Along the Cove” recalls Jerry Lee Lewis in its rollicking piano rhythm as Dylan coolly croons absolute nonsense that is nonetheless amazingly affecting because of its earnestness: “Down along the cove, we walked together hand in hand / Ev’rybody watchin’ us go by knows we’re in love, yes, they understand.” Even more breathtaking is the album’s closer, “I’ll Be Your Baby, Tonight”. The scene is late at night-as simple guitar strums as a steel guitar and harmonica spin out their soft down-home yarns of intimacy and good-humor. Dylan’s voice is tender and loving to the point of sounding ridiculous. It is a comforting vision of two lovers escaping from the world in a comfortable room with a good bottle of wine. After an album devoted to the exploration of apocalypse and salvation, big questions and no answers, /John Wesley Harding/‘s finale begins with the simple exhortation of a lover for peace of mind: “Close your eyes, close the door / You don’t have to worry, anymore / I’ll be your baby tonight.”

Dylan explored the power and mystery and love more fully on his next album, 1969’s /Nashville Skyline/ (who can forget the bold claim of “I Threw It All Away”: “Love is all there is, it makes the world go ‘round”?), but it was never as affecting as it was on “I’ll Be Your Baby, Tonight”. /John Wesley Harding/ draws its immense power from its contrasts-part graveyard folk, part shmoozy country; part biblical allegory, part love lyric; part myth, part fable; part grave condemnation, part whispered nothing. All of these dichotomies are set up and subverted, constantly frustrating the listener looking for an easy or simple message. Somehow all these disparate strands coalesce into an album of intricate variety and complexity. In its 12 short tracks, it tells the story of the vast sweep of human experience. There is death, there is fear, there is love, there is redemption sought for, there is redemption gained. While its flashy predecessors (/Highway 61 Revisited/ and /Blonde on Blonde/) often claim the bulk of admiration, John Wesley Harding sharp, clear vision and tight execution make it Dylan’s most cohesive album, that should not be overlooked. Chances are it won’t be overlooked precisely because of its seeming agelessness. In terms of the trajectory of Dylan’s career it was completely new, but in a deeper, more intuitive sense, it sounded as if it had been around forever, addressing questions that have been around forever and always will be.

Another Review:

Music Review: Bob Dylan - John Wesley Harding

Written by David Bowling

Published September 20, 2008

See this link for the complete review : http://blogcritics.org/archives/2008/09/20/210516.php

Blonde On Blonde found Bob Dylan taking rock ‘n’ roll to places where it had not previously gone. However, in July of 1966 Dylan was in a motorcycle accident and disappeared from public view. He would only perform live twice in the next three years and that would be at two memorial concerts for Woody Guthrie at Carnegie Hall. He would spend a great deal of time and effort cloistered with The Band in Woodstock, New York, recording dozens of songs. These recordings would be bootlegged for years until finally released as The Basement Tapes in 1975. Interestingly no songs recorded during these sessions would appear on Dylan’s next release.John Wesley Harding was released December 27, 1967 without much fanfare. Dylan would issue no singles from this album, yet it would be his highest charting album to date reaching number 2 on the national charts.

John Wesley Harding was an about face from Blonde On Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited. Dylan returned to playing his acoustic guitar backed by only Charlie McCoy on bass and Kenneth Buttrey on drums, plus some occasional steel guitar by Pete Drake. It would also be a very focused effort for Dylan. Dylan let his imagination run wild on Blonde On Blonde but there is a more unified feel here. The songs were melodic and tended not to stray from traditional structures. But this was still Dylan and his use of imagery would remain intact which looked toward a horizon that only he could see.The big surprise of John Wesley Harding was its spiritual nature and especially the use of Old Testament imagery. As such, it is a lovely and calming album that at its end finds Dylan moving in a gentle country direction.

Here is a great page that compiles excerpts from numerous reviews: http://www.answers.com/topic/john-wesley-harding-album

I will reprodce a couple of interesting paragraphs from this page but please follow the link to see the whole compendium.

1. Bob Dylan returned from exile with John Wesley Harding, a quiet, country-tinged album that split dramatically from his previous three. A calm, reflective album, John Wesley Harding strips away all of the wilder tendencies of Dylan's rock albums -- even the then-unreleased Basement Tapes he made the previous year -- but it isn't a return to his folk roots. If anything, the album is his first serious foray into country, but only a handful of songs, such as "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight," are straight country songs. Instead, John Wesley Harding is informed by the rustic sound of country, as well as many rural myths, with seemingly simple songs like "All Along the Watchtower," "I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine," and "The Wicked Messenger" revealing several layers of meaning with repeated plays. Although the lyrics are somewhat enigmatic, the music is simple, direct, and melodic, providing a touchstone for the country-rock revolution that swept through rock in the late '60s.

2. Most of the songs on John Wesley Harding are noted for their pared-down lyrics. Though the style remains evocative, continuing Dylan's strong use of bold imagery, the wild, intoxicating surreality that seemed to flow in a stream-of-consciousness fashion has been tamed into something earthier and more crisp. "What I'm trying to do now is not use too many words," Dylan said in a 1968 interview. "There's no line that you can stick your finger through, there's no hole in any of the stanzas. There's no blank filler. Each line has something." According to Allen Ginsberg, Dylan had talked to him about his new approach, telling him "he was writing shorter lines, with every line meaning something. He wasn't just making up a line to go with a rhyme anymore; each line had to advance the story, bring the song forward. And from that time came...some of his strong laconic ballads like 'The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest.' There was no wasted language, no wasted breath. All the imagery was to be functional rather than ornamental." Even the song structures are rigid as most of them adhere to a similar three-verse model.

The dark, religious tones that appeared during the Basement Tape sessions also continues through these songs, manifesting in language from the King James Bible. In The Bible in the Lyrics of Bob Dylan, Bert Cartwright cites more than sixty biblical allusions over the course of the forty minute album, with as many as fifteen in "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest" alone. An Old Testament morality also colors most of the songs' characters.

In an interview with Toby Thompson[1] in 1968, Dylan's mother, Beatty Zimmerman, mentioned Dylan's growing interest in the Bible, stating that "in his house in Woodstock today, there's a huge Bible open on a stand in the middle of his study. Of all the books that crowd his house, overflow from his house, that Bible gets the most attention. He's continuously getting up and going over to refer to something."

3. "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest" is perhaps the album's most enigmatic song, structured as a (possibly insincere) morality play. The song details Frankie Lee's temptation by a roll of ten dollar bills from Judas Priest. As Frankie thinks it over, he grows anxious from Judas's stare. Eventually, Judas leaves Frankie to mull over the money, telling him he can be found at "Eternity, though you might call it 'Paradise'." After Judas leaves, a stranger arrives. He asks Frankie if he's "the gambler, whose father is deceased?" The stranger brings a message from Judas, who's apparently stranded in a house. Frankie panics and runs to Judas, only to find him standing outside of a house. (Judas says, "It's not a house ... it's a home.") Frankie is overcome by his nerves as he sees a woman's face in each of the home's twenty-four windows. Bounding up the stairs, foaming at the mouth, he begins to "make his midnight creep." For sixteen days and nights, Frankie raves until he dies on the seventeenth, in Judas's arms, dead of "thirst." The final two verses are the most impenetrable. No one says a word as Frankie is brought out, no one except a boy who mutters "Nothing is revealed," as he conceals his own mysterious guilt. The last verse moralizes that "one should never be where one does not belong" and closes with the song's most quoted lines, "don't go mistaking Paradise for that home across the road."

The album's next three songs all feature one of society's rejects as the narrator or central figure. "Drifter's Escape" tells the story of a convicted drifter who escapes captivity when a bolt of lightning strikes a court of law. "Dear Landlord" is sung by a narrator pleading for respect and equal rights. "I Am a Lonesome Hobo" is a humble warning from a hobo to those who are better off.

4. "I asked Columbia to release it with no publicity and no hype, because this was the season of hype," Dylan said. Clive Davis urged Dylan to pull a single, but even then Dylan refused, preferring to maintain the album's low-key profile.

In a year when psychedelia dominated popular culture, the agrarian John Wesley Harding was seen as reactionary. Critic Jon Landau wrote in Crawdaddy Magazine, "For an album of this kind to be released amidst Sgt. Pepper, Their Satanic Majesties Request, After Bathing at Baxter's, somebody must have had a lot of confidence in what he was doing ... Dylan seems to feel no need to respond to the predominate trends in pop music at all. And he is the only major pop artist about whom this can be said."

The critical stature of John Wesley Harding has continued to grow. As late as 2000, Clinton Heylin wrote, "John Wesley Harding remains one of Dylan's most enduring albums. Never had Dylan constructed an album-as-an-album so self-consciously. Not tempted to incorporate even later basement visions like 'Going to Acapulco' and 'Clothesline Saga,' Dylan managed in less than six weeks to construct his most perfectly executed official collection."

--