Hist 199 Postwar Japan: No Regrets for our Youth (1946)

--Some Comments by Kevan Smoliak, adapted and supplemented by me.

See complete discussion at: http://kurosawainreview.blogspot.com/2009/05/no-regrets-for-our-youth-1946.html

Background:

No Regrets for Our Youth was Kurosawa's fifth film, and his first after the end of World War II. The end of the war was a bit of a godsend for Kurosawa, who during the war produced films that were subjected to the utmost scrutiny by the nationalistic Japanese censors.

New censors from the American occupation force would come in to replace the strict Japanese. Although these censors would be far more lenient than the Japanese, they would be quick to deny the release of any film that showed any sort of anti-American sentiment.

No Regrets is an interesting film among Kurosawa's repertoire due to its strong female lead character. Kurosawa's films generally don't feature women in the main role unlike the films of another Japanese great Kenji Mizoguchi.

"Women simply aren't my specialty," Kurosawa once remarked to the legendary Japanese film scholar Donald Richie.

Kurosawa states in his autobiography that the title of the film was born out of the popular post-war phrase in newspapers, "No regrets for our ---".

The film suffered from two setbacks during production. First, against Kurosawa's will the script was re-written because another script was submitted based on the same story. Second, there was a strike at Toho Studios where the film was being made.

The film takes place over a period of 10 years, beginning in 1933. The film progresses from 1933, to 1938 and then finally to 1941 to the end of the film. These sections act as separate acts within the story, a storytelling technique Kurosawa was fond of.

The first act deals more with the social problem aspect of the picture. The students, in their anger over the loss of academic freedom and rise of an expansionist government, take to the street and riot. The students are eventually stopped by the police and the riots stop.

This is the point in the film where the story of Yukie and the two men with whom she is choosing between starts to come to the forefront.

Itokawa, driven by his family duty, sheds his activist ways and pursues his education again while Noge, the stronger-willed of the two is arrested for his work.

In 1938 Yukie is 25 and still living at home, but she has become restless. Yukie's father has begun to give free legal advice. When Itokawa brings a newly freed Noge back to visit Yukie, old feelings are again brought up in her.

After they leave Yukie resolves to move to Tokyo. This is where the film jumps another few years up to 1941. Yukie has begun working in Tokyo when she happens to run into Itokawa who tells her Noge is now working and living in Tokyo as an activist against the government. [More precisely, he works for an Institute for Research on East Asian Problems so technically is not engaging in any illegal behavor. But it is understood that he is secretly working on "plans" that could help Japan avoid getting into a war with China.]

Yukie is reluctant to see Noge but he eventually finds her sulking in front of his workplace. After a discussion of the dangers of Noge's work they decide to wed.

Noge is eventually ambushed by police but will die in his cell before his trial can take place.

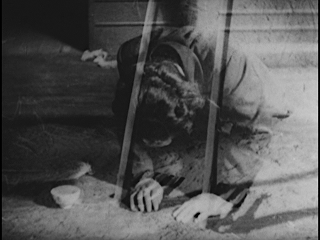

A distraught Yukie decides it is her duty to go to Noge's parents. His parents have been leading a life in solitude, going out in the night to do their work for fear they will be chastized over what their son has done.

Yukie begins to work in the fields with Noge's mother where they eventually bond. After the war Yukie chooses to remain in the village with Noge's parents, seeing herself as an activist within the community.

After the war ends, Yukie's father is reinstated at the university as well, and calls upon the students to remember what Noge has done for them.

[Yagihara's remarks FROM THE FILM: "There is one man more than anyone else, I wish could have seen this day. He fought for academic freedom. Moreover, he risked everything in the service of Peace and Prosperity for Japan. He was the Pride of our University. His name was Noge Ryukichi and he is no longer with us. However, there was a time when Noge sat right over there where you gentleman are now sitting (pointing to a spot). I hope and expect that many, many more men like Noge will arise from your ranks...And that is why I have decided, despite my age, to return to teaching." (wild applause!]

Analysis:

Even with the problems that the picture suffered during production, the film still conveys a powerful message.

Visually the film does not stand out among Kurosawa's work, but there are glimpses of shots and style that Kurosawa would use in later pictures.

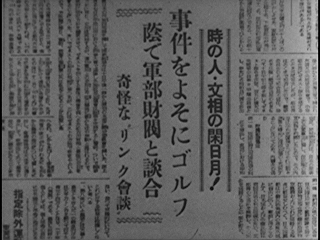

One example is during the first act when the students are rioting. The audience is presented with a montage of students taking to the streets mixed with shots of newspaper headlines that Kurosawa would later employ in his 1960 film The Bad Sleep Well.

Kurosawa also uses some not so subtle symbolism in No Regrets as well. While Yukie is learning flower arrangement in Tokyo she suddenly plucks all of the flowers from her bowl and begins to tear off three petals representing herself, Itokawa and Noge. She proceeds to throw these petals into the bowl, saying that the previous arrangement wasn't a true showing of her expression.

Also, when Yukie is pleading with Noge's parents to stay with them and work, a high angle shot of Yukie's hands is superimposed with a similarly angled shot of two farming tools with finger-like claws.

Another example of this superimposition technique that began with the French Impressionist film movement occurs when Yukie is interrogated and subsequently imprisoned. While she is sitting in her cell, a clock pendulum is superimposed sweeping accross the frame, intensifying the passage of time.

One more sequence shows Yukie's emotions represented through this technique. When she is conflicted about whather or not to see Noge when Itokawa brings him to visit, she is shown either gripping a door handle or pressing herself against a door.

The use of this technique may have come out of Kurosawa's love of silent films. In the silents, it was almost always only the visuals that could be used to convey emotions. Kurosawa would later explore his love of silent film in Rashomon.

Another important technique in conveying emotion is music. Music would become much more important to Kurosawa a few films after No Regrets. In No Regrets the music works as film music does in most other films, merely adding an emotional note to a film or to punctuate a scene.

This is true for the non-diegetic (soundtrack) but not always for the diegetic (music played in the film world). For example, when Yukie plays the piano, she plays what she feels. The first time she plays she is expressing her anger over the situation with the students and her father. The second time she plays a sad song that turns angry, showing her confliction. Finally, in one of the last scenes, she looks down at her hands and she comments on how they are no longer fit for the piano, they are merely workers hands now.

Transformation is another main theme of the film. With the passage of time, Yukie and others begin to change.

"People change a lot in five years," Itokawa says before telling Yukie she is becoming more ladylike. Yukie does go through numerous physical and emotional transformations throughout the film.

Yukie certainly does what Noge told her she needed to do in the beginning of the film, which is to grow up.

When they finally do marry and begin to live in a home of their own, Kurosawa shows several shots of flowers, signaling a re-birth in their lives.

Kurosawa is quick to point out that not all is well in their lives, as he presents several scenes of Yukie breaking down while sewing a kimono for Noge and while watching a funny movie in a theater.

The American censors must have loved this film. Its themes of winning freedom of speech and expression must have certainly resonated with their goals for the newly occupied country.

While many of the characters' personas are not set in stone throughout the movie, the wartime Japanese government and police force are portrayed as the lowest of the low.

The latter is represented by Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura as the police chief who takes pleasure in delivering what he calls "good news" about the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Although the film moves from the social to the more Kurosawa-like humanistic side by focusing on Yukie, the message of freedom from oppression is still clear in the end.

This is opitimized in the titles before the final scenes that say,

"The war is lost but freedom is restored."

There is another message that is even more important for Kurosawa in this picture, however. That is the one contained in the title. Several times in the movie Yukie and Noge discuss how they have no regrets. Noge even has a saying, "No regrets in my life."

Throughout the film Yukie continues to forge ahead, never looking back. She too has no regrets. When Itokawa comes to visit Yukie at Noge's parents' home he tells Yukie that Noge went down the wrong path, a claim that angers Yukie who promptly defends Noge and sends Itokawa away.

In the end Yukie takes on a tremendous sense of duty. A duty not only to her dead husband, but to his family and their community. Even though she has done her duty by staying with his family, she resigns to remain with them.

Commentary added by Loftus:

[Her mother wants Yukie to come back home and live with her Mother and Father. She asks pleadingly: "If Noge's parents understand his actions now, haven't you accomplished your goal? "No," replies Yukie. "I've put down roots in that village." And her hands, she tells her mother, as they rest of the piano, "They look so out of place on a piano now. Besides, there's still so much work left to do there. Their lives, especially the women's lives, are brutally hard. If I can improve their lot even a little, my life will be well-spent. You could say I'm the shining light of the rural cultural movement." He smile is radiant and genuine.

"You were born to suffer, my child," her mother says. "Why? I've never seen myself that way. And I'm not just putting on a brave face." Again, her smile is broad and genuine. "Noge always used to say, 'No 'regrets in my life'. That's the source of my happiness."]

In one of the final shots Yukie stands at the edge of the water surrounding the mountain that she visited at the beginning of the film. She stands solemly, looking out over the water, before boarding a truck back to the village.

She sends a message that through perseverance and duty you can overcome hardships and obtain freedom. But in the end, with Yukie bound to the villagers and the family that she has sworn to serve, is she really free?

Kurosawa never says more than that the last 20 minutes of the film were the part that was re-written, but perhaps this was the contradiction he was seeking to avoid.

Additional Commentary by Loftus:

Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, one of the most eloquent writers on modern Japanese film, has quite a bit to say about No Regrets in his study of Kurosawa (Duke, University Press, 2000). He places his discussion of the film in the context of three things:

1) The postwar debate about "Subjectivity"--or the shutaisei-ronsô 主体性 論争),

2) The Twin Ideas of Victim Consciousness and

3) Conversion Narratives.

The debate over subjectivity (主体性) was taking place around the same time that Kurosawa was working on No Regrets. It involved scholars, public intellectuals, philosophers, especially from Kyoto University, journalists and social activists. It was a way to probe the difficulty Japanese had with establishing a subject position from which their involvement in militarism can be explained logically and without contradictions. The lesson of the Fifteen Year War seemed to be--at least to some people in the postwar period--that "no society not based on a genuine shutaisei--a true 'subjectivity' or 'autonomy' at the individual level--could hope to resist the indoctrinating power of the state." (Quoted in John Dower, Embracing Defeat, p. 157). In other words, Japan needed genuine authentic "subjects" with historical agency in order to resist the rise of militarism and fascism.

What does it mean to talk about a “Subject” with historical agency? Seems like their are many possibilities. Here are some. Pick your favorite?

1. Clearly, it refers to a person who is capable of carrying out and being responsible for an action, rather than being the object that is acted upon. In the simplest terms, it has something to do with discovering one's authentic self through social action.

2. In the context of history, to become a “subject” means to become an agent of history, someone who is the conscious architect of events, rather than someone who is simply buffeted and structured by the conditions in which they find themselves.

3. As filmmaker and critic Oshima Nagisa expresses it, “The shutaiteki individuals are engaged in an effort to change a specific social situation in which they find themselves, and to transform themselves in relation to that situation.” (Quoted in Yoshimoto, 128) Whatever these conditions might be, they constitute the forces that either enhance, shape, or oppose the influence of the social structure on the individual.

4. So, to put in another way, each of us encounters a given social structure, determined by the time and place we live--against which we must define ourselves and carve out a space for meaningful social action.

5. At least in theory, then, every person has the capacity to achieve individual agency...at least to some extent. There will always be limitations on the degree of agency we can manifest depending on the prevailing cultural, gendered, ethical, and economic restraints that we face.

6. This is why human agency is always "conditioned" by the time and place in which the individual agent lives and functions. To the extent that we are able to explore and develop our own Subjectivity however, are able to to “transform [our]selves” as Oshima put it, our chances of changing the world around us increase.

(NOTE: We will encounter similar ideas about individual agency being "constrained" by actual social conditions when we read Changing Lives, Ch. 1 where we will find historian Gabriele Spiegel suggesting that historical actors might be "constrained but not wholly controlled" by the social reality in which they must operate. So, historical acrtors are constrained by existing social and political conditions? Yes! By all means! But "wholly controlled," by them, leaving no opportunity for meaningful action? No! This is the small opening which makes social action and individual agency possible.)

The challenge for prewar Japanese was that the historical givens--the social and political conditions in which they weere forced to operate--did not allow them a lot of room in which to maneuver. According to the Meiji Constitution (1889), the people and therefore individual actors could not be "soveriegn subjects." Sovereignty was something clearly located in the person of the Empeor. So when it came to defining the term Democracy in the 1900s, the common term minshushugi (民主主義), which locates sovereignthy (主) in the people (民), did not conform to Meiji Constitutional Law which placed the locus of sovereighty in the person of the emperor.

However, there was a clever politics professor and journalist, Yoshino Sakuzô, who tried to get around this limitation the 1918 by coining a new term for Democracy, calling it minponshugi 民本主義 or the people as being central or "fundamental to" (本) both government and society. In effect, Yoshino was saying that "Government For the People" was very possible; and Government could even be conducted or carried out "By the People." But what it could not be in the legal context of the Meiji Consitution is "OF the People," So, it was a nice "work around!"

But the government had a nice counter move for this: it submitted to the Diet and passed the Peace Preservation Law in April of 1925 (shortly after a new Universal Male Suffrage Act was also passed) which held in Article 1 that:

Anyone who organizes a group for the purpose of changing the national polity (国体, kokutai) or of denying the private property system, or anyone who knowingly participates in said group, shall be sentenced to penal servitude or imprisonment not exceeding ten years. An offense not actually carried out shall also be subject to punishment.

In other words, any Socialist or Marxist or utopian Anarchist group that might envision a world in which neither capitalism, nor the monarchy, nor even the nation-state were deemed essential...this would stand in violation of the rule of law. Which is why the real hisotrical figure on whom Professor Yagihara was modeled, Takigawa Yukitoki, was fired from his position at Kyoto Imperial University for giving a lecture on the topic of Leo Tolstoy's final novel, Resurrection. Even though Tolstoy was a Christian and not a Marxist, he was charged with spreading Marxist ideas presumably jjust he was a Russian writer and Russia had undergone a Marxist-Leninist Revolution in 1917. Tolstoy had been drawn to the ideas of Anarchism, so perhaps his ideas were considered incompatible with the "Kokutai" (国体), the "National Polity" for this reason. The Kokutai operated as a tautology: Japan was unique and expressed its unique "political essence" in its monarchy. According to rthe founding myths, Japan's Emperor could be traced all the way back to the age of the gods, to the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, which is what made him "sacred" and "semi-divine"; and since nowhere else in the world could there be such claims of august orgins, this is what intrinsically determined Japan's uniqueness.

Two years after the Kyoto University Incident, in 1935, the very respected Professor of constituional law at Tokyo Imperial University, Minobe Tatsukichi, was also hounded from his position becuase of his widely accepted "Organ Theory" of the Meiji Constitution. This theory held that since the Emperor was mentioned specificially in the Constitution, he was thereby being defined by language under the Law and so, in that sense, the Emperor was simply one of the several "organs" of the prewar government like the Diet, the Bureaucracy, the Cabinet, the various Ministries, etc.

It is a legally sound and quite reasonable argument that had been widely accepted in the teens and twenties; but by the toxic 1930s, this kind of cosmopolitan worldview was no longer tenable. It was an insult to the "sacred and inviolable" nature of the monarchy to think that there could be any legal limitations on the Emperor's sacred authority.

Couldn't one think of the film, No Regrets for our Youth, as an exploration of what genuine subjectivity or individual angency might have looked like in 1930s Japan? After all, the film methodically takes us through the period of the Fifteen Year War, beginning with the Manchurian Incident in 1931, and ending with defeat on August 15, 1945, and it displays time markers across the screen repeatedly--1932, 1933, 1938, 1941, and finally, 1945. So, doesn't it seem as though the filmmaker is interested in revisiting the prewar years in order to look closely and see how all this came about? What was missing from Japanese people in the 1930s that prevented them from resisting the rise of Fascism? Why were they not more effective in resisting the growth of militarism and ultra-rightism? Did they lack a sufficient sense of their own individual autonomy and agency, their own political and historical subjectivity?

Noge, of course, is the main character in the film who manifests genuine subjectivity. He knew that the university faculty were too idealistic and hopeful that they would prevail because they had "Right" on their side. This was naive. According to Professor Yagihara's emotional lecture at the end of the film, after the war was over, Noge was the one who "Fought for academic freedom. He risked everything for the peace and prosperity of Japan. He was the pride of this university!" And, true to Yagihara's beliefs, Noge had to pay the ultimate price for his actions--he had to sacrifice everything--because he took Responsbility for what he was doing, for trying to develop a plan to help "solve the China Probelm" without making it necessary for Japan to invade China and become enmeshed in a pointless, destructive war. At the dinner with Noge and Itokawa at Yukie's house after Noge had been released from prison for his underground activities, he freely admitted that he had undergone an "ideological reversal" or a "tenkô," aka, a "conversion" meaning that he renunced of his old beliefs and pledged support for the emperor. But the wise Professor Yagihara was skeptical that Nogre was "sincere" about this pledge. He did it simply to get out of prison so he could resume his dedication to the cause of hindering military expansionism and keeping Japan out of war.

As Noge and Yukie reunite and become a couple, she seeks to learn from him how to develop this kind of subjectivity and agency on her own, to learn how to become a genuine historical subject with independence, integrity, and autonomy. This is clearly what she wants: she tells her father in the "leaving home scene" that she wants to get out into the world and do something, to experince what it feels like to really be alive. As it is, she feels that she is not really living; she does not have that something, that cause, with that "passion," (jônetsu), that fiery spirit that Itokawa can clearly see in her face when he encounters her for the last time near the end of the film. Admitting that he cannot compete with her on that level, Itokawa asks her to allow him to visit Noge's grave but she refuses. She does not believe Noge's spirit would be happy to see him. She now knows how to be resolute and to stand up for herself and for what is right.

Yukie had desperately wanted to live a life with meaning, with purpose, in which she can have integrity, and to live with that commitment she found with Noge. She had sought a cause to which she could dedicate herself "body and soul," and that was what a life lived "without regrets" was all about. Now, after the war, after Noge's death, she wants to continue creating a life with meaning, with value, but now it will be in the village with Noge's parents. She can discover something "shining" there but she knows it will not blaze so brightly that she will be in danger of becoming blinded.

At the end of the film, she states clearly that she has found that sense of commitmeant and meaning in her life in the countryside. She has become "the shining light of the rural cultural movement," and if she can do even the littlest thing to improve the life of ordinary women in the countryside--which is "brutally hard"--then she will feel satisfied.

The film critic and author of a biography of Kuosawa, Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, has something to say about Yukie's unique "self-transformation" or "conversion" over the course of the film. He writes that

The film does not present her an an ideal character from the beginning but shows the process of her transformation or conversioin from a strong-willed but somewhat capricious woman who does not know where to direct her inner energy to a highly independent responsible individual who fights against wartime militarism and promotes postwar democracy. The attraction of Yukie lies in her abilitty to convert herself into an uncomprmising defender of personal liberty and democreacy perecisly when she is most threatened by the oppreessive power of the militarist government and everyday fascism. (122)

These kinds of "conversion narratives" are important n the postwar discourse but as Yoshimoto points out later,

In conversion narrative, memory of the past was not simply erased; instead, nostalgia for the prewar and celebration of the postwar as a radical new beginning co-existed simultaneously. What guaranteed this coexistence was 'August 15, 1945,' which functioned as a nodal point of fantasy that bound together two mutually contradictory moments of affirmation and denial. In other words, in the disavowing process, 'August 15, 1945,' was transformed into a fetish. (132)

We see how Kurosawa clearly uses this pivotal date to claim that "The war is lost but freedom is restored," and thereby to create a "historical disjunction separating a militarist Japan and a democratic one," a date he emblazons on the screen, along with the accompanying words:

"The Day of Judgment--defeat! And the day liberty is restored."

It seems as though Yoshimoto is doubtful as to whether liberty can actually be restored in just one instant, and suspects that Kurosawa feels a great deal of ambivalnce about this himself. (131-132)

A convincing case can be made, however, as Yoshimoto does, that the main character Yukie does undergo a signficant transformation, possibly a kind of conversion, in the film. Her subjectivity does change, and perhaps Kurosawa was also hopeful that postwar Japanese film viewers would also experience something similar in the course of watching his film, as well. Yukie has learned some of those tough lessons that her father had warned her about. Freedom requires great struggle and sacrifice. And, she has changed. She is not the same flighty, impulsive young girl she was when Noge admonished her that she needed to grow up early in the film. She had once been excessively naive; now, she no longer is.

Yoshimoto thinks that we can see evidence for this in the iconic image of her hands which reflect her inner thoughts and psychology as much as her (tormented) facial expressions do. We see her hands first as icons gathering flowers, playing piano, but later destroying her own ikebana, and then finally becoming rough and calloused from farm work. Eventually, they are no longer suitable for piano playing: "They look so out of place on a piano now," she says to her mother who desperately wants her to come home and resume life the way it was. But she cannot. When Itokawa visits her in the countryside, she is washing her muddy, calloused hands in a flowing brook. These are not the hands with which she began the film.

So Yukie does transform in the course of the film. But look at how Kurosawa also slips in his other concern about nostalgia, melancholy and conflict as they appear on her face during the final scenes of the film. At times she radiates happiness as she talks with her mother in her old home in Kyoto, seated at the piano, but when she returns to the village at the end, what do we see? Ambivalence? Isn't her face clearly pained and melancholic when she pauses by the stream on her way back to the village? She tells her mother that she has put down roots in the village; that there is much work that still awaits her there. The life of the farmers, especially the women, is brutally hard she asserts. "If I can improve their lot even a little, my life will be well spent." Smiling broadly to her mother--even beaming, you might say, she tell her, "You can say that I am the shining light of the rural cultural movement."

She seems very happy but her mother counters with the remark that she was born to suffer. Still smiling broadly Yukie asks "Why? I have never seen myself that way. Noge always used to say, 'No regrets in life': "Kaerimite, kui no nai seikatsu" (顧みて悔いのない生活) and his hoarse whisper persistently reminds her of this at various points in the film. But then a shadow passes over her face, and it becomes more melancholic as she faces the keyboard. "That is the source of happiness in my life," she says, referring to the "No Regrets" philosophy that she and Noge shared. But how happy is she?

It brings to mind the self-reflections of Okabe Itsuko whom we will meet soon in Ch. 1 of Changing Lives. She writes about how in the powerful words uttered by her fiance--"the war is a mistake"--she was able to find meaning in her life; that is how she is able to have her "today." Likewise, Yukie's memories of Noge and of their life together, and of their shared philosophy of "Live Life without Regrets," are what allows her to have her "today," and also her tomorrow, her future with the villagers, where she stands up with them as the "shining light of the rural cultural movement."

Next in the film, there is a dissolve with a superimposition of her profile back at the piano, hunched over the keyboard while she is also standing looking at the river, her back to us, her suitcase by her side. This is followed by a cut to a scene of her sitting peacefully by the stream while the next generation of postwar students comes along, whistling the same song as Noge once had, and then singing, extolling the beauty of flowers and the virtues of Kyoto and its revered center of learning, the University. Seeing the postwar students on Mt. Yoshida, stepping across the rocks to ford the stream just as she, Itokawa and Noge once had done many years ago, her face registers nostalgia but also deep melancholy.

In fact, the camera comes in for a close-up shot and lingers on her face for almost a full 30 seconds while we hear the students coninuing to sing. But this not a happy or excited face. Then this scene dissolves into the country road where she stands with her suitcase and soon the trucks come rumbling by.

The third truck picks her up, and when she is pulled up into the back of the truck by the villagers who are already on board, there is an awkward moment. The camera focuses on the villagers first, one by one, as they bow to her and smile, evincing their embarrassment and chagrin over their past conduct, uncomfortable about the horrible way they treated her. Yukie is a little hesitatant, too, but she finally settles upon a smile. But it is just a brief smile, perhaps a small one. Is it a little hesitant or weak? It is nothing like the radiant smile she shared with her mother back in Kytoto. And then the camera pulls away quickly as the truck moves off down the road leaving her figure a dark silhouette. In this shot, there is nothing like the lingering 30 seconds of profound melancholy that we just saw at the stream. We know full well that Yukie has made a sacrifice to return to the village and sacrifices are always hard.

Aren't we left to wonder just how happy she will really be? Writing of the final scene, Yoshimoto says it should "be celebratory but hardly appears so." (134) Yukie seems uncertain, ambivalent, troubled, or at the very least, conflicted. Perhaps this range of emotion, and the moving back and forth between them revealing both happiness, and sadness, and the way she wrestles and grapples with these emotions--might this be precisely what Kurosawa wanted his audience to see? That way, they could know that they are not alone in their own ambivalences and contradictory emotions; nor are they alone in their own struggles.

Yoshimoto concludes his chapter with the following observation:

More than anything else in the film, I believe this image of Yukie's face registers Kurosawa's resistance to the Occupation's attempt to propagate their version of recent Japanese history. Kurosawa continued to pursue more fully his covert resistance to the Occupation in his subsequent postwar films. (134)

The Occupation authorites had been forced to come up with some analysis of prewar Japanese society to understand what went wrong with it--how Japan had been hurtled down the road to militarism and imperialism--in order to come up with their prescriptions for remaking or remolding Japan. But, inevitably, this analysis had to be superficial. Many of the occupiers knew next to nothing about Japan so how could their understanding of Japanese History and Society have any real depth?

Kurosawa experienced for himself many of the contradictions that accompanied the prewar and postwar years and we see the traces of these on the faces and in the lives of his characters in No Regrets. In the prewar years, he had been forced to make films that met certain thematic requirements but within those parameters, he still tried to make films that mattered. In the postwar years, too, the Occupation authorities approved certain themes (they loved his anti-militarism, his focus on strong, courageous, independent characters, and his elevation of the status of women) but postwar filmmakers were not allowed to depict the war in any way, and their scripts needed to be approved by the authorities in advance. Didn't both scenarios involve regimes of truth and control? How could he not feel some ambivalnce? Many have pointed out the hypocrisy of the Occupation's devotion to democratic principles but yet had no hesitation about denying those freedoms to Japanese writers and filmmakers if they did not conform to the Occupation guidelines. This was an enormous contradiction that Kurosawa had to work out in his early films.

Also, looking ahead, we will see in Loftus, Changing Lives, pp. 3-5, some more comments about subjectivity and agency. We should remember and reflect upon how those comments might tie in with this discussion.

See also these pertinent comments from a Sense of Cinema Review:

Akira Kurosawa’s fifth feature film, and his first following the end of World War II, Waga seishun ni kuinashi (No Regrets for Our Youth) is amongst the most fascinating of the director’s early works. Based upon the 1933 Kyoto University Incident in which Professor Takikawa Yukitoki was removed from his position due to his supposedly “red” beliefs, the film is also one of the few examples of a Kurosawa film dealing with a contemporaneous socio-political issue in a direct manner.

Despite its setting, however, the major focus of No Regrets for Our Youth is not the Kyoto University Incident itself, but the manner in which the event affects the lives of Kurosawa’s characters. The director forgoes engaging in explicit political commentary in favour of focusing upon a character-driven narrative. Granted, the socio-political scenario depicted within the film is certainly integral to the narrative and must not be understated but, as always, characterisation is key to Kurosawa’s artistic success.

Apart from its political content, one major feature setting No Regrets for Our Youth apart from the director’s larger body of work is that it marks the only Kurosawa film to feature a female protagonist. In Yukie (Setsuko Hara), we are given a heroine who is both complex and challenging. Initially childish and emotionally volatile, Yukie undergoes a form of personal development allowing her to see more clearly the world in which she lives. The 13 years covered by the film, 1933 to 1946, feature her evolution from emotional immaturity to wisdom.

Toward the beginning of the film Yukie lives in denial of the social situation affecting her father and friends. In the midst of a discussion about how since the Manchurian Incident, the militarists have been pushing Japan toward a dull-scale war in China, Yukie wants to talk about pleasant things and beautiful things in the world. This kind of dark, morbid talk spoils her mood. She must certainly be aware of the whole situation given its direct impact upon her own life, but outwardly she attempts to maintain an illusion of cheerfulness.

Even the news of her father’s professional termination and her encounter with a fallen soldier while hiking with her friends appears to have little real effect upon her. But Yukie’s illusion is ultimately shattered when the object of her affection, Noge (Susumu Fujita), is imprisoned for his political activity. Her decision to leave behind her parents and secret admirer, Itokawa (Akitake Kono), are ostensibly based in her desire to begin her own life as an adult, but it also suggests her wish to be closer to the type of lifestyle experienced by the adventurous Noge.

Visually, No Regrets for Our Youth is among Kurosawa’s most compelling films. Kurosawa does not attempt to stylistically reflect the volatile social and political conditions which form the backdrop of the film, but rather provides a more introspective visual atmosphere. In contrast to later masterpieces such as Rashomon (1950) and Shichinin no samurai (The Seven Samurai, 1954), No Regrets for Our Youth is much more meditative in its form; even poetic at times. From the beginning of the film Kurosawa provides us with images of quiet contemplation: Yukie running through a field of flowers; a montage featuring Yukie being playfully pursued through a forest by Noge and Itokawa; a close-up of three flowers floating in a bowl of water (reflecting the triangular relationship between Yukie, Noge and Itokawa) at Yukie’s flower arrangement class. A later montage illustrating Yukie‘s visible anguish following her mother’s request that she come downstairs to see Noge off before his departure to China, resembles aspects of the psycho-dramas of Maya Deren. Kurosawa uses a series of quick cuts to convey the different emotions experienced during by Yukie during this brief moment of decision.

from: the Sense of Cinema, http://sensesofcinema.com/2010/cteq/no-regrets-for-our-youth/