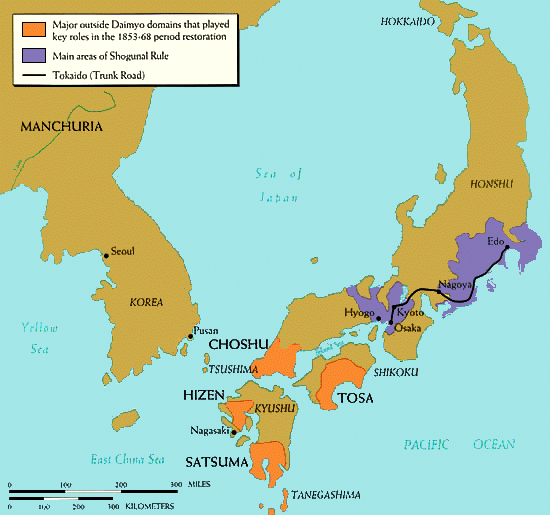

The Meiji Restoration occurred when leaders from several southwest TOZAMA domains or “han” such as Satsuma, Choshu, Hizen and Tosa (SAT-CHO-TO-HI), took up arms against the 15th Tokugawa Shogun, a family that had ruled Japan for the past 267 years. They moved from the southwest toward Kyoto where the emperor resided in the Imperial Palace in December of 1867. There they fought a decisive battle in which western trained "mixed" units from Satsuma and ChoshU defeated the Shogun's troops.

On 4 January 1868, the restoration of Imperial rule had already been formally proclaimed. Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu had earlier resigned his authority to the emperor, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders.The Tokugawa Shogunate had officially ended.However, while Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist. Moreover, the Tokugawa family remained a prominent force in the evolving political order,[8] a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable. They referred to it as "the rebirth of Ieyasu," and they wanted no part of it.

The Sat-Cho leaders, especially Saigo Takamori, coerced the court into ordering the confiscation of Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s land. This led to an armed clash between bakufu troops and the Sat-Cho army when the latter wanted to eliminate their influence over the young Emperor Komei. The 15,000-strong Shogunal army outnumbered the Satsuma-Chōshū army by 3:1 but that Sat-Cho Army was fully modernized with Armstrong howitzers, Minié rifles and one Gatling gun. They won the day and in April 1868, the Shogun’s castle was peacefully handed over to the now “Imperial” forces and the emperor changed his location from Kyoto to Edo now renamed Tokyo. (Based largely on a Wikipedia article)

This is basically IT!

A political challenge to the old regime was successful; a coup d'etat or a revolution "restored" the emperor to power, which they called ôsei-fukko, or, literally, the restoration of imperial authority. But the monarch never did rule directly. He was expected to accept the advice of the core young leadership group that had overthrown the shôgun, and who were now called "Councillors" as they were members of the Dajôkan or "Council of State," but also known as the "Oligarchs" because they constituted a small ruling elite that did not share power very widely.

It was from this group that a small number of ambitious, able, and patriotic young men from the middle and lower ranks of the samurai class emerged to take control and establish the new political system. At first, their only strength was that the emperor accepted their advice and several powerful feudal domains provided military support. They moved quickly, however, to build their own military and economic control. By July 1869 the feudal lords had been requested to give up their domains, and in 1871 these domains were abolished and transformed into prefectures of a new unified central state structure. Thsi was HUGE! A big deal. The old hybrid, divided polity was gone; in its place, a new government with strong central powers to Tax, Conscript for a national Army, set up a Nationwife Compulsory Educational System, an end tot he Samurai class itself anf the creation of a modern Army and Navy, and Banking System....

When the Meiji emperor was restored as head of Japan in 1868, the nation was a militarily weak country, was primarily agricultural, and had little technological development. It was controlled by hundreds of semi-independent feudal lords. The Western powers - Europe and the United States - had forced Japan to sign treaties that limited its control over its own foreign trade and required that crimes concerning foreigners in Japan be tried not in Japanese but in Western courts. When the Meiji period ended, with the death of the emperor in 1912, however Japan had

· a highly centralized, bureaucratic government

· a constitution establishing an elected parliament

· a well-developed transport and communication system

· a highly educated population free of the old feudal class restrictions

· an established and rapidly growing industrial sector based on the latest technology; and

· a powerful army and navy

Japan had regained complete control of its foreign trade and legal system, and, by fighting and winning two wars (one of them against a major European power, Russia), it had established full independence and equality in international affairs. In a little more than a generation, Japan had exceeded its goals, and in the process had changed its whole society. Japan's success in modernization has created great interest in why and how it was able to adopt Western political, social, and economic institutions in so short a time.

One answer is found in the Meiji Restoration itself. This political revolution "restored" the emperor to power, but he did not rule directly. He was expected to accept the advice of the group that had overthrown the shôgun, and it was from this group that a small number of ambitious, able, and patriotic young men from the lower ranks of the samurai emerged to take control and establish the new political system. At first, their only strength was that the emperor accepted their advice and several powerful feudal domains provided military support. They moved quickly, however, to build their own military and economic control. By July 1869 the feudal lords had been requested to give up their domains, and in 1871 these domains were abolished and transformed into prefectures of a unified central state.

The feudal lords and the samurai class were offered a yearly stipend, which was later changed to a one-time payment in government bonds. The samurai lost their class privileges, when the government declared all classes to be equal. By 1876 the government banned the wearing of the samurai's swords; the former samurai cut off their top knots in favor of Western-style haircuts and took up jobs in business and the professions.

The armies of each domain were disbanded, and a national army based on universal conscription was created in 1872, requiring three years' military service from all men, samurai and commoner alike. A national land tax system was established that required payment in money instead of rice, which allowed the government to stabilize the national budget. This gave the government money to spend to build up the strength of the nation.

***

So, by any interpretation, the story of the Meiji Restoration is a story of profound changes in a country’s political, social, economic and international orientation that came about in response to the intrusion by western imperialist powers. One could argue that there are two components to this response to the armed intrusion by the west into East Asia:

1. Respond by acquiring the most up-to-date technology, especially military hardware and tactics, while leaving society pretty much as it was currently organized along so-called "traditional" lines, i.e., retaining core political, economic, social institutions and ethical practices, buttressed by ideological beliefs. The issue was that the western powers were propelled to expand outward in search of trade and other finanacial opportunities because of the Industrial Revolutions experienced back at home. The Industrial Revolution produced steady economic growth rates which allowed people to live in much better material conditions than they had in pre-industrial times. Once they know about this, most people want this for themselves, they want economic growth and increased wealth. But this proces is often inimical to a country's traditions and the traditional way of life that supports old institutions. That is why it represents such a profound challenge to the old way of doing things.

2. Respond by not only introducing new technologies, but by grafting on all kinds of new economic, political, and social institutions--schools, new governing styles and organizational principles and administrative practices. These usually bring about fundamental changes to society, social codes and classes, educational institutions, etc. In other words, this response recognizes that the challenges posed by western Imperialism required wholesale economic, political and social changes. Not all traditional societies were willing to do that, to go that far. They were attached to their oldtraditions, and did not want to give them up. China was the primary case in point. So we can say that Japan both modernized AND westernized their institutions while China did not. China came to stand for a negative model of what not to do.

So, this is the story of the Meiji Restoration in a nutshell but it begs the question, what, precisely, is the nature of these momentous historical changes? Figuring out our answers to this question is going to be the primary task for the first unit of Hist 381, but really, perhaps, it is a question that will persist through most, if not all, of the units into which this course is subdivided.

If you want more details about the fall of the Bakufu, here are some excerpts from the Wikipedia pages on the "Boshin War."

Chōshū had long been a thorn in the Bakufu's side. Many young "loyalist" samurai congregated there and vilified the Bakufu for compromising its own rules by making concessions to the barbaraiasns, Following a coup within Chōshū which returned to power the extremist factions opposed to the Shogunate, the Shogunate announced its intention to lead a Second Chōshū expedition to punish the renegade domain. This in turn prompted Chōshū to form a secret alliance with Satsuma. In the summer of 1866, the Shogunate was defeated by Chōshū, leading to a considerable loss of authority. In late 1866, however, first Shogun Iemochi and then Emperor Kōmei died, respectively succeeded by Yoshinobu and Emperor Meiji. These events "made a truce inevitable."[17]

On November 9, 1867, a secret order was created by Satsuma and Chōshū in the name of Emperor Meiji commanding the "slaughtering of the traitorous subject Yoshinobu."[18] Just prior to this however, and following a proposal from the daimyo of Tosa, Yoshinobu resigned his post and authorities to the emperor, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders.[19] The Tokugawa Shogunate had ended.[20]

While Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist. Moreover, the shogunal government, the Tokugawa family in particular, would remain a prominent force in the evolving political order and would retain many executive powers,[21] a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable.[22] Events came to a head on January 3, 1868 when these elements seized the imperial palace in Kyoto, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old Emperor Meiji declare his own restoration to full power. Although the majority of the imperial consultative assembly was happy with the formal declaration of direct rule by the court and tended to support a continued collaboration with the Tokugawa (under the concept of "just government" (公議政体?, kōgiseitai)), Saigō Takamori threatened the assembly into abolishing the title "shogun" and order the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands.[23]

Although he initially agreed to these demands, on January 17, 1868 Yoshinobu declared "that he would not be bound by the proclamation of the Restoration and called on the court to rescind it."[24] On January 24, Yoshinobu decided to prepare an attack on Kyoto, occupied by Satsuma and Chōshū forces. This decision was prompted by his learning of a series of arsons in Edo, starting with the burning of the outerworks of Edo Castle, the main Tokugawa residence. This was blamed on Satsuma ronin, who on that day attacked a government office. The next day shogunate forces responded by attacking the Edo residence of the daimyo of Satsuma, where many opponents of the shogunate, under Takamori's direction, had been hiding and creating trouble. The palace was burned down, and many opponents killed or later executed.[25]

Having formed a secret and illegal alliance, the Statsuma-Chōshū troops decided to move against the Shogunate. The 15,000-strong Shogunal army outnumbered the Satsuma-Chōshū army by 3:1, and consisted mostly of men from the Kuwana and Aizu domains, reinforced by Shinsengumi irregulars. Although some of its members were mercenaries, others, such as the Denshūtai, had received training from French military advisers. Some of the men deployed in the front lines remained armed in archaic fashion, with pikes and swords. For example, the troops of Aizu had a combination of modern soldiers and samurais, as did the troops of Satsuma to a lesser level, whether the Bakufu had almost fully equipped troops, and Chōshū troops were the most modern and organized of all.[13] According to Conrad Totman: "In terms of army organization and weaponry, the four main protagonists probably rank in this order: Chōshū was best; Bakufu infantry was next; Satsuma was next; and Aizu and most liege vassal forces were last". [14]

It is important to note that there was not a clearly defined intent to fight on the part of the Shogunal troops, attested to by the fact that many of the men in the vanguard had rifles which were empty. Motivation and leadership on the part of the Shogunate also seems to have been lacking.[15]

Although the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma were outnumbered, they were fully modernized with Armstrong howitzers, Minié rifles and one Gatling gun. The Shogunate forces had been slightly lagging in term of equipment, although a core elite force had been recently trained by the French military mission to Japan (1867–1868). The Shogun also relied on troops supplied by allied domains which were not necessarily as advanced in terms of military equipment and methods, composing an army that had both modern and outdated elements.

The British Navy, generally supportive of Satsuma and Chōshū, was maintaining a strong fleet in Osaka harbor, a factor of uncertainty which forced the Shogunate to maintain a significant part of its forces to garrison Osaka rather than commit it to the offensive towards Kyōto.[16] This foreign presence was related to the very recent opening of the ports of Hyōgo (modern Kobe) and Ōsaka to foreign trade three weeks earlier on 1 January 1868.[17] Tokugawa Yoshinobu himself was in bed with a severe chill, and could not participate directly to the operations.[18]

TobaFushimi Battle near Kyoto

Scene of the Battle of Toba-Fushimi. Shogunate forces are on the left, including battalions from Aizu. On the right are forces from Chōshū and Tosa. These are modernized battalions, but some of the forces were also traditional samurai. (especially on the Shogunate side)

The Shogunal forces moved in the direction of Toba under the command of vice-commander Ōkubo Tadayuki, making a total of about 2,000 to 2,500 troops.[21] At around 1700, the Shogunal vanguard, made up largely of about 400 men of the Mimawarigumi, armed with pikes and some firearms, under Sasaki Tadasaburo, approached a Satsuma-manned barrier post at the Koeda bridge (小枝橋), Toba (located in what is now part of Minami-ku, Kyoto).[22] They were followed by two infantry battalion (歩兵), rifles empty as they did not really expect a fight, under Tokuyama Kōtarō, and further south by eight companies from Kuwana with four cannons. Some Matsuyama and Takamatsu troops and a few others were also participating, but Bakufu cavalry and artillery seem to have been absent.[23] In front of them were entrenched about 900 troops from Satsuma, with four cannons.[24]

After denying the Shogunal force permission to pass peacefully, the Satsuma forces opened fired from the flank. These were to be the first shots of the Boshin War. A Satsuma shell exploded on a gun carriage next to the horse of Shogunal commander Takigawa Tomotaka, causing the horse to throw Takigawa and bolt. The startled horse ran wild, throwing the Shogunal column into panic and disarray.[25] The Satsuma attack was forceful and quickly sent the Shogunal troops in disarray and retreat.[26]

On 27 January 1868, Shogunate forces attacked the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma, clashing near Toba and Fushimi, at the southern entrance of Kyoto. Some parts of the 15,000-strong Shogunate forces had been trained by French military advisers, but the majority remained medieval samurai forces. Meanwhile, the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma were outnumbered 3:1 but fully modernized with Armstrong howitzers, Minié rifles and a few Gatling guns. After an inconclusive start,[26] on the second day, an Imperial pennant was remitted to the defending troops, and a relative of the Emperor, Ninnajinomiya Yoshiaki, was named nominal commander in chief, making the forces officially an imperial army (官軍, kangun?).[27] Moreover, convinced by courtiers, several local daimyo, up to this point faithful to the Shogun, started to defect to the side of the imperial court. These included daimyo of Yodo on February 5, and the daimyo of Tsu on February 6, tilting the military balance in favour of the Imperial side.[28]

On February 7, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled Osaka aboard the Kaiyō Maru, withdrawing to Edo. Demoralized by his flight and by the betrayal by Yodo and Tsu, Shogunate forces retreated, making the Toba-Fushimi encounter an Imperial victory, although it is often considered the Shogunate forces should have won the encounter.[29] Osaka Castle was soon invested on February 8 (on March 1, Western calendar), putting an end to the battle of Toba-Fushimi.[30]

Adapted from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boshin_War