(adapted from Kumiko Sato's web pages)

Captain Genji danced 'Blue Sea Waves." His partner, Tô-no-Chûjô , certainly stood out in looks and skill, but beside Genji he was only a common mountain tree next to a blossoming cherry, As the music swelled and the piece reached its climax in the clear light of the late-afternoon sun, the cast of Genji's features and his dancing gave the familar steps an unearthly quality. His singing of the verse could have been the Lord Buddha's kalavinka voice in paradise. His majesty was sufficiently transported with delight to wipe his eyes, and all the other senior nobles and Princes wept. When the verse was over, when Genji tossed his sleeves again to straighten them and the music rose once more in response, his face glowed with a still-greater beauty. (128-129)

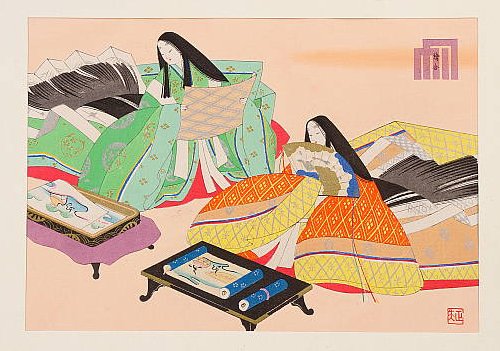

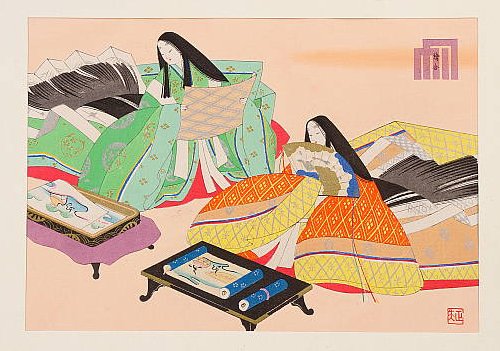

The contest remained undecided on into the night. The Left [Genji's side] had one more turn, and when the Suma scrolls appeared, To-no-chujo's heart beat fast. His side, too, had saved something special for last, but this, done at undisturbed leisure by a genius at the art, was beyond anything. Everyone wept, Prince Hotaru, the first among them. Genji's paintings revealed with perfect immediacy, far more vividly than anything they had imagined during those years when they pitied and grieved for him, all that had passed passed through his mind, all that he had witnessed, and every detail of those shores that they themselves had never seen. He had added here and there lines in running script, Chinese or Japanese, and although these did not yet make it a true diary, there were such moving poems among them that one wanted very much to see more. No one thought of anything else. Emotion and delight prevailed, now that all interest in the other paintings had shifted to these. The question answered itself: the Left had won. (316-317)

Woolf had enjoyed nine chapters by the author she described as “the quiet lady with all her breeding, her insight, and her fun,” but her assumption that the rest would prolong them in kind was understandably wrong. She had not read enough to catch the significance of “the crux of the entire work,” nor could she have noted the early signs of a still greater, related theme derived from Japanese myth: that of fraternal rivalry for dominion over the land, and of the younger brother’s subjection of the elder….

However, I admit that I myself probably expected more from the tale, in the way of “strong meanings,” precisely because it has been held up so long as a great masterpiece. My personal background and limitations being what they are, however, the meanings that readers seemed to find in it did not impress me as very “strong.” Their relationship to the narrative content of the tale also escaped me. That is why I felt impelled to comprehend for myself the work I had translated, and why this effort has constituted, for me, a second stage in the project of translation. No one, centuries ago, saw in the tale tragedy consequent upon Aristotelian error, nor do people now. No one sees either, in the relationship between Genji and his elder brother Suzaku, that between the two brothers in the myth of Hosonuseri and Hikohohodemi. Nothing could therefore demonstrate more vividly the tale’s richness and greatness, or its capacity to stand as a world classic, than the way the narrative itself has supported and rewarded my effort to read it from outside its own culture. Did the author “intend” it to be read as I read it? I have no idea. However, I am satisfied that The Tale of Genji excludes neither tragedy nor a powerful succession struggle and its aftermath, and that since a reader like me can find these in it, they can also serve to describe what The Tale of Genji is about more intelligibly, for readers of English, than talk of love affairs and sensibility—talk that tends to turn the tale at best into a novel…engaging but structurally weak….

I had just understood for the first time the significance of a passage in “Kiritsubo.” This passage makes it clear that although Suzaku, the heir apparent and elder brother, has expressed interest in Aoi, Aoi’s father has decided nonetheless to give her to Genji, a mere commoner. [See p. 14] No one just starting to read the tale in English, or perhaps in Japanese either, is likely to understand that the minister’s decision is highly unusual, still less to grasp its intensely political character. Suzaku is entitled to assume that if he wants Aoi, she is his. However, Aoi’s father snubs him in favor of Genji, the younger brother with an uncertain future. This is the first sign of the political and personal struggle that will dominate the tale.

This struggle is founded in myth, but the myth takes the brothers’ story only through the triumph of the younger over the elder, who remains little more than a cipher. The Tale of Genji goes further. “Fujinouraba” (Chapter 33) ends with Suzaku’s complete subjection. As retired emperor, he and Emperor Reizei, Genji’s secret son, pay a formal visit to Genji, as though to a greater monarch, at Genji’s recently completed Rokujô estate. Precisely at that moment, the “arc” of Genji’s life tips downward. At the start of the next chapter, Suzaku invites Genji to marry his beloved daughter, Onna Sannomiya [The Third Princess]. The result is disaster for himself and for Genji. Call it karma or call it folly, the subjected elder brother wrecks his own last years just as surely as he wrecks those of his triumphant younger brother, and still without ever regaining the upper hand. If the “horror, terror, or sordidity” that Virginia Woolf missed in the first nine chapters are present anywhere in the book, it is in these chapters that follow, no doubt with interspersed digressions, when the awful, step by step consequences of Genji’s acceptance of Onna Sannomiya unfold. For “horror,” one might mention Kashiwagi’s ghastly presence at the party that Genji traps him into attending, and Genji’s killing glance; for “terror,” the scene when Rokujô’s resentful spirit speaks; and, for “sordidity,” Kashiwagi’s pathetic appropriation of Genji’s wife.

The story culminates in the terrible moment when Onna Sannomiya [ 女三宮, the Third Princess] calls her father down from his mountain temple and, over Genji’s protests, has him ordain her as a nun. The two men exchange no harsh words, but by this time harsh words would only attenuate the nightmare. Genji has catastrophically failed Suzaku, and Suzaku’s attachment to his daughter has ruined the rest of his life.

Once, while I was translating such scenes as these, I rushed out of my study to exclaim to my wife, “This is beyond anything! If The Tale of Genji is known worldwide for anything at all, it should be known for this! This is what lifts it into the company of the few greatest works of literature ever written!” I did not yet understand consciously how one event followed from another in this part of the tale, or how the narrative had managed to produce this effect. I now see, however, how rightly Virginia Woolf demanded of the greatest literature moments of “terror, horror, or sordidity” and wrote of missing, in what she had so far read of the tale, a “root of experience” that she thought had been “removed from the Eastern world so that crudeness is impossible and coarseness out of the question.” No, in The Tale of Genji that “root of experience,” those transcendent touches of “crudeness” or “coarseness,” which anchor grace and beauty in lived human truth, are there after all. They take the tale to the heights of the sublime. (from: http://www.jpf.org.au/onlinearticles/profile/royalltyler-genji-lect-english.pdf)

The spark that brings Murasaki fully to life in The Tale of Genji flashes in the “Miotsukushi” chapter (our Ch. 14, "The Pilgrimage to Sumiyoshi"), when Genji offends her with his talk of the lady at Akashi and the daughter conceived there during his exile.

“There I was, [she] thought, completely miserable, and he, simple pastime or not, was sharing his heart with another! Well, I am I!”

Her ware wa ware (“I’m me!”) sharply affirms the distinctness of her existence.

Akiyama Ken wrote that studying Murasaki, more than any other character, reveals the essence of the tale. She is Genji’s private discovery and his personal treasure. Her fate in life depends so entirely on him that she might be a sort of shadow to him, without a will of her own, and yet at this moment, and later ones like it, she resists him. The pattern of give and take between the two is as vital to the unfolding of their relationship as it is to the development of the tale itself. Murasaki’s precise social standing vis-à-vis Genji and the court society they inhabit is essential, too. These interrelated issues in turn bear on the great crisis of Murasaki’s life: the disaster that strikes both her and Genji when Genji agrees to marry the Third Princess (“Wakana One”). Their relationship has its crises, and the marriage to the Third Princess strains it nearly to the breaking point, but it lasts until the loss of Murasaki leaves Genji a mere shell of the man he once was.

Scholar Shimizu Yoshiko writes of three critical scenes punctuate the relationship and calls them them Murasaki’s “perils.” They are

1) Murasaki’s hurt when she learns about the lady from Akashi (“Akashi” and “Miotsukushi”);

2) her fear when Genji courts Princess Asagao (“Asagao”); and

3) her shock when Genji marries the Third Princess (“Wakana One,” “Wakana Two”).

These scenes follow a clear trajectory. Each time Genji talks to Murasaki about another woman who is or has been important to him she resents it, her anger upsets him, and his effort to calm her miscarries because it is at least in part blind and self-serving. Each time there is more at stake for Genji, and the impact on Murasaki is more serious. It is therefore reasonable to see dramatic progression from one of these scenes to the next.

Many have wondered why Genji seeks with Akashi, Asagao, and the Third Princes,s the tie that so disturbs Murasaki, when he already has in Murasaki a wife who meets his personal ideal and for whom he cares deeply. The answer seems to be that Genji’s desire for all three involves less erotic acquisitiveness than thirst for heightened genealogical prestige.

First, Genji’s tie with Akashi, and the consequent birth of their daughter, opens for him the way towards that highest advantage accessible to a commoner: to be the maternal grandfather of an emperor. Reaching this peak—an aspect of his destiny fostered by her father’s devotion to the Sumiyoshi deity and announced by prophetic dreams—does not depend entirely on his will, but it requires from him a cooperation that he gives gladly. What Murasaki sees, however, is attachment to a rival who, to make things worse, gives him a child when she herself cannot.

Second, Asagao and then the Third Princess promise to round out Genji’s success—one that might be called less political than representational. By the time he courts Asagao seriously, let alone by the time he accepts the Third Princess, his supremacy is secure. He does not need them politically, but he still wants one and then the other in order to seal his increasingly exalted station.

Thus Genji is a flawed man like others, despite his gifts, and for him public ambition comes into conflict with private affection. Murasaki’s quality makes her his personal, but not his social equal, and her value to him, as well as her valuation of herself despite his slights, makes this conflict a theme that runs through the tale.

The Crisis over Akashi

In his twenty-sixth year Genji goes into exile at Suma, leaving Murasaki at home in charge of his affairs. The cause of his exile was his reckless passionate affair with Oborozukiyo, the Kokiden's cobsort's younger sister, and daughter of the Minister of the right, the enemy faction. When they got got in the act, so to speak, the Minister of the Right was furious and Oborozukiyo was banned from court for a while. The emperoor really wanted her and on p. 239 the text says:

His Majesty, who still thought highly of her, ignored the vicious gossip and kept her constantly with him as before, now chiding her for this or that, now asserting ius love, and he did so with great beauty and grace; but alas, her heart only had room for memories of Genji.

Once when there was music, His Majesty remarked, "His absence leaves a void. I expect many others feel it even more than I do. It is as though all things have lost their light"; and he went on, "I have not done as my father wished. The sin of it will be upon me." Tears cam to his eyes and, helplessly, to hers as well...His manner was so kind, and he spoke from such depth of feeling, that her tears began to fall. "Ah yes," he said, "for which of us do you weep?" (239-240)

Genji is the "Shining One" and when he is absent--off in Suma--a light seems to depart from the court. later in the Tale, when Genji dies, light seems to dissipate from the world, as well. But note the tenderness and the depth of feeling that is captured here, and how no one can really fault Genji for who and what he is: someone very special, a once in a millenia phenomenon.

[The above comments added by Loftus.}

The three-year separation of Genji from the Court and his beloved Muraskai is painful (she is only nineteen when he returns), but it never occurs to her that he might not be faithful. Meanwhile, he misses her desperately and hesitates to take the opportunity that the Akashi lady’s father is so eager to press on him. Still, he yields in the end to the Akashi Novice’s urging, to the exotic enchantment of the place, and to the lady’s personal distinction, so unexpected in a provincial governor’s daughter. He returns from Akashi understandably full of his experience and especially of thoughts of the lady and the child she is soon to bear.

Genji feels “deeply content” once reunited with Murasaki, and he sees “that she would always be his this way.” At the same time, however, “his heart went out with a pang to [Akashi], whom he had so unwillingly left.”

He began talking about her, and the memories so heightened his looks that [Murasaki] must have been troubled, for with “I care not for myself” she dropped a light hint that delighted and charmed him. When merely to see her was to love her, he wondered in amazement how he had managed to spend all these months and years without her, and bitterness against the world rose in him anew.[41]

Despite the wonder of rediscovering Murasaki, anticipation of the birth and then the thought of his new daughter prolong the enchantment. A prophetic dream has already let him know that the little girl is a future empress and that in her his own fortunes are at stake.

However, Murasaki does not yet know about the birth, and Genji does not want her to hear of it from someone else. To mask all it means to him he behaves like a guilty husband, first claiming indifference and a commendable resolve to do his tedious duty, then passing to diversionary reproaches.

“So that seems to be that,” he remarked. “What a strange and awkward business it is! All my concern is for someone else, whom I would gladly see similarly favored, and the whole thing is a sad surprise, and a bore, too, since I hear the child is a girl. I really suppose I should ignore her, but I cannot very well do that. I shall send for her and let you see her. You must not resent her.”

She reddened. “Don’t, please!” she said, offended. “You are always making up feelings like that for me, when I detest them myself. And when do you suppose that I learned to have them?”

“Ah yes,” said Genji with a bright smile, “who can have taught you? I have never seen you like this! Here you are, angry with me over fantasies of yours that have never occurred to me. It is too hard!” By now he was nearly in tears.

Fearing Murasaki’s rebuke, Genji takes the offensive and obliges her to defend herself instead. Still, it is true that she does not quite understand. The child means more to him than the mother, and in time he will have Murasaki adopt her for that reason. Meanwhile, Murasaki remembers “their endless love for one another down the years, …and the matter passed from her mind.”

In the ensuing silence Genji goes on, half to indulge his feelings and half to pursue loyal confidences. In so doing he manages to hurt Murasaki after all.

“If I am this concerned about her,” Genji said, “it is because I have my reasons.You would only go imagining things again if I were to tell you what they are.” He was silent a moment. “It must have been the place itself that made her appeal to me so. She was something new, I suppose.” He went on to describe the smoke that sad evening, the words they had spoken, a hint of what he had seen in her face that night, the magic of her koto; and all this poured forth with such obvious feeling that his lady took it ill.

There I was, she thought, completely miserable, and he, simple pastime or not, was sharing his heart with another!

Well, I am I! (Ware wa Ware).

She turned away and sighed, as though to herself, “And we were once so happy together!” (289)

...For all her innocence, sweetness, and grace, she still had a stubborn side to her, and when she was offended, as now, her wrath had a quality so delicious that he only enjoyed her the more. (290)

How can our heart not go out to Murasaki when she asserts that "I am I" and chastises Genji for trying to tell her how she feels. She can take care of that herself! She knows who she is and how she feels.

The pattern of this conversation recurs in the two other crisis passages yet to be discussed. There, too, once the danger seems to have passed Genji indulges in reminiscing about his women, especially Fujitsubo in the second and Rokujō in the third. In each case someone then becomes angry: Murasaki here, then the spirit of Fujitsubo, and finally the spirit of Rokujō. The role played by the three women in these scenes suggests their critical importance to Genji himself.

The injury Murasaki feels is of course painful, and her response springs from a fine quickness of spirit, but the scene is still touched by the lyrically beautiful anguish of those exile years. She is hurt but not yet in danger. No provincial governor’s daughter, not even one as unusual as Akashi, can really threaten her.

Murasaki and the Third Princess make a contrasting pair, as many scholars have noted. The circumstances of the Third Princess’s birth and upbringing, described early in “Wakana One,” also suggest a mirror-image contrast with Genji himself. Suzaku’s daughter is visibly conceived as, so to speak, an anti-particle dangerous to both.

Most Japanese scholars, and all writing in English,[75] agree that Genji accepts the Third Princess because of her link to Fujitsubo. Some also point out an element of pity for Suzaku. Ōasa Yūji even suggested that Genji hopes for a new Murasaki and called the marriage a mistaken attempt on Genji’s part to relive the past. Fukasawa Michio, who saw the key theme of the tale in the stark contrast between the glory of Genji’s Rokujō estate and the miseries caused by the arrival of the Third Princess, held that the “occasion” of these miseries is none other than Murasaki’s jealousy.

It is Genji’s acceptance of the Third Princess, not Murasaki’s jealousy (her growing wish to disengage herself from Genji), which causes the misfortunes of “Wakana One” and beyond. However, Murasaki’s feelings are certainly central to these misfortunes. Akashi was no threat, even if the inexperienced Murasaki thought she was. Asagao resembled distant storm clouds that melted into the sky. However, the Third Princess actually moves into the Rokujō estate and she far outranks even Asagao. “By birth [Asagao] is worth what I am,” Murasaki assures herself in “Asagao” (in other words, “My father is a prince, too!”); but she knows that that is not the whole truth and must conclude, “I shall be lost if his feelings shift to her.”[77] The Third Princess allows not even that spark of hope. Insignificant in her person, she is of crushing rank. Murasaki yields in silence. Senseless protest would only demean her further.

“The story,” Washburn writes, “has been read as a moral and religious guide, as a source for historical data on court society, as a feminist text and post-feminist text, as a marker of cultural literacy and national identity.” The fact that such a long and abstruse work has been translated into English so many times speaks eloquently of that work’s essential appeal across time and cultural divides." [See Ian Buruma's article in the New Yorker discussing the Genji and Washburn's translation.]

I could only look back wistfully on the experience of translating a book of folktales by the French writer Henri Pourrat. French being a language I actually know, I just typed. Genji was very different, but I persevered until I actually got to the end. Perhaps that is success enough for one lifetime.

At the heart of that appeal is surely Genji himself, the story’s beautiful, feckless, slightly bumptious main character, the refined and endlessly priapic son of the Japanese emperor. Court machinations bar him from the actual exercise of his royal prerogatives – he goes about life technically a commoner in rank – but he’s the brother, lover, and father of emperors and empresses, and his occasional egalitarian gestures don’t fool any of Murasaki Shikibu’s many dozens of characters, and they don’t fool our author either, who dotes on her hero despite the many foibles with which she’s invested him.

immensely scholarly but also, somehow, uncannily readable, helpful without being pedantic, clarifying without ever simplifying. Gone are the Edwardian paraphrases of Arthur Waley; gone too is the somewhat flat-footed gait of the Edward Seidensticker; and the occasionally forbidding purity of the Royall Tyler is softened and colored in around the edges. It’s an amazingly cheering performance, a Genji to last a century. And if W.W. Norton should see fit to create an electronic version, your poor terrified metacarpals will scarcely notice the pages flying by. (See "The Book and the Boy," http://www.openlettersmonthly.com/the-book-and-the-boy/)

What Genji does in this scene is outrageous, not to mention implausible outside fiction. Many recent readers have roundly condemned him for it. But does it harm Murasaki? Considering the realities of her life and her prospects, the answer is no, on the contrary. At her father's house she would be (from her stepmother's controlling standpoint) no more than an unwanted stepchild, a sort of Cinderella. All her stepmother's efforts go to promoting her own daughters, who, needless to say, lack Murasaki's many qualities. The stepmother would soon be defending her daughters against the threat that Murasaki represents and relegating Murasaki as much as possible to the outer darkness. Mursasaki would of course be married off in the end, but to a relative nobody. Her beauty and her abundant gifts would go to waste. In contrast Genji treasures them throughout her life. No husband approved by her father could possibly have become Honorary Retired Emperor or made her an Empress's adoptive mother.

Still, there remains the question of how Genji actually consummates his marriage with her. That he rapes her has been self-evident to many recent readers, for whom the matter is so clear and so reprehensible that nothing further need be, or even should be, said about it. This is what happens. Having obtained Murasaki after all, Genji treats her with great affection but also with unfailing tact and respect. Despite sleeping with her (literally) every night when at home, he never betrays the slightest wish to press himself upon her. Meanwhile, she grows up. Then Genji's original wife dies, under the circumstances alluded to above.

In the previous chapter, when her mourning period is over, Genji looks at Murasaki with fresh eyes and sees that the time has come. He therefore tries in various, discreet ways to arouse her interest in changing the nature of their relationship. However, he fails completely. His hints pass right over her head. She cannot even wonder whether or not to consent, since she has no idea what he is talking about. The intimacy already established between her and Genji throws her incomprehension into sharp relief. Is such innocence even possible under her circumstances? Or has Genji misjudged her stage of development? With respect to the first question, one need only recall that the tale is fiction. The reader has no reasonable choice but to accept what the narrative says.

As for the second, Murasaki is certainly still very young—right around fourteen or fifteen. However, this was a normal age for marriage in the world of the tale. In fact, many characters were married at much earlier ages...and years later her adopted daughter will give birth to a future Emperor, apparently without difficulty, at the age of twelve or thirteen. There is no reason to believe that Genji is wrong by the standards of his time. He seems even to have been unusually patient.

Then what does the author mean by Murasaki's failure to understand him? The answer should be clear already. Her incomprehension proves her quality and promises her future greatness as a lady. For her to say yes would be unworthy of her; for her to say no would place Genji, hence herself, in a very difficult position; and for her to say either would compromise her by showing that she does know what he is talking about. Her utter innocence is what proves her supreme worth. As in the case of Suetsumuhana it is up to Genji to act, and he does. Yes, Murasaki remains furious with him for some time thereafter, but her anger passes, and beyond the chapter in which all this takes place the narrative never alludes to it again. The experience is inevitable, but once it is over, it is over. Its only significant consequence is that now Murasaki can begin her adult life with Genji. That life that will bring her various trials, as anyone's is likely to do, but also great happiness; and in the end it will lift her, for the reader, to a height of grandeur beyond anything her yes or no could have achieved.

...One of Kaoru's salient traits is to be unusually considerate of the opposite sex, at least when the prospective partner is of high standing.[15] He had his chance once with Ôigimi (a night that he managed to spend alone with her, over her protests), but he never seized it, as Genji or Niou would have done. Unlike any other man in the tale, he insists on refraining from making love to Ôigimi until she herself allows him to do so. At first one smiles with approval, as many readers have done in centuries past; but then one begins to understand his ghastly mistake. He is out of touch with reality. If he had acted decisively during that night, regardless of Ôigimi's local feelings on the subject, he would have committed himself to her and her to him. He would have taken the decision out of her hands, and she would not have died. Far from it: considering how deeply he and she actually felt about each other, they might really have lived happily ever after.

See Royall Tyler, "Marriage, Rank and Rape in The Tale of Genji" Intersections, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue7/tyler.html

Bai Juyi also wrote intensely romantic poems to fellow officials with whom he studied and traveled. These speak of sharing wine, sleeping together, and viewing the moon and mountains. One friend, Yu Shunzhi, sent Bai a bolt of cloth as a gift from a far-off posting, and Bai Juyi debated on how best to use the precious material:

Bai's works were also highly renowned in Japan, and many of his poems were quoted and referenced in The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu.[15]

Bai Juyi is considered one of the greatest Chinese poets, but even during the ninth century, sharp divide in critical opinions of his poetry already existed.[17] While other poets like Pi Rixiuonly had the highest praise for Bai Juyi, others were hostile, like Sikong Tu (司空圖) who described Bai as "overbearing in force, yet feeble in energy (qi), like domineering merchants in the market place."[17] Bai's poetry was immensely popular in his own lifetime, but his popularity, his use of vernacular, the sensual delicacy of some of his poetry, led to criticism of him being "common" or "vulgar". In a tomb inscription for Li Kan (李戡), a critic of Bai, poet Du Mu wrote, couched in the words of Li Kan: "...It has bothered me that ever since the Yuanhe Reign we have had poems by Bai Juyi and Yuan Zhen whose sensual delicacy has defied the norms. Excepting gentlemen of mature strength and classical decorum, many have been ruined by them. They have circulated among the common people and been inscribed on walls; mothers and fathers teach them to sons and daughters orally, through winter's cold and summer's heat their lascivious phrases and overly familiar words have entered people's flesh and bone and cannot be gotten out. I have no position and cannot use the law to bring this under control."[18]

Bai was also criticized for his "carelessness and repetitiveness", especially his later works.[19] He was nevertheless placed by Tang poet Zhang Wei (張為) in his Schematic of Masters and Followers Among the Poets (詩人主客圖) at the head of his first category: "extensive and grand civilizing power."[19]

Students are often confused about three basic facts in Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji:

1) The Tale of Genji is written about two hundred years after Bai Juyi’s poem about Yang Guifei;

2) Genji is a fictional character; and

3) All of The Tale of Genji occurs in Japan.

It is useful to explain how Murasaki knew this Chinese source. Murasaki lived in the Heian Period (794-1185). She started writing about Genji about the year 1000. Kyoto, the capital city of Japan at that time, was modeled after the Chinese capital of Chang’an, with similar parallel streets, gardens, and architecture. The life of aristocratic Japanese women was also somewhat similar to that of Tang Chang’an, even though that court life had largely disappeared in China by the year 1000. Aristocratic women in Heian Japan were highly educated, clearly for the purposes of marriage alliances. Murasaki and some other court women, such as the famous writer Sei Shonagon, could read poetry written in Chinese characters, even if they knew no spoken Chinese. Manuscripts from China entered Japan and were recopied, including illustrations. See also:

http://www.thedrunkenboat.com/juyi.html

http://www.iz2.or.jp/english/what/