|

Mill’s On Liberty |

|

|

|

|

|

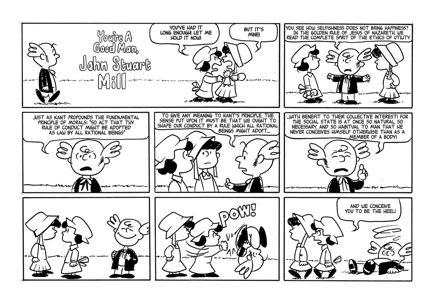

Mill asserts: ‘One very simple principle’: the

only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a

civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others’ (p.13/Hp.9) - harm to self is ok. - reason and even remonstrate with

person, but do not compel or subject to other painful consequences - also known as The

liberty principle or harm principle |

|

Liberty of

... (p.15/ Hp.11-12) 1. thought, conscience, inner mental life,

and expression (hence also of press) (ch.2) 2. action, following own tastes and

pursuits, framing own plan of life (ch.3) 3. association, or uniting |

|

Put

positively … (p.16/ Hp.12) -

“The only freedom which

deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long

as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to

obtain it. Each is the proper guardian

of his own health, whether bodily, or mental and spiritual. Mankind are greater gainers by suffering

[tolerating] each other to live as seems good to themselves, than by

compelling each to live as seems good to the rest.” |

|

How

absolutely does he mean all this? “No society …” (p.16/ Hp.12) |

|

|

|

Six

Qualifications regarding the scope of Mill’s Argument in On Liberty: |

|

|

|

|

|

[ 1. ] Mill’s argument

depends on the historical context

– or relative stage of progress in human organization – regarding the struggle/balance between liberty and

authority (p.5/ Hp1). |

|

|

|

Mill’s

contemporary 19th British context was a democratic republic that: a.

recognizes political liberties and rights b.

observes constitutional and consensual checks on Government action c.

and ensures that rulers and elected are temporary. Thus,

the limits of political authority were effectively settled. (Hp.2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

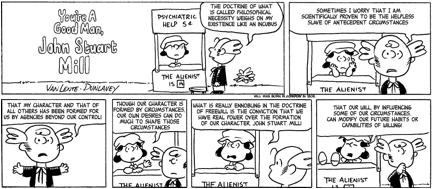

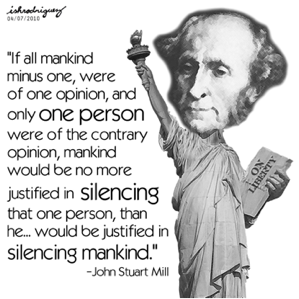

[ 2 ] Mill’s Argument refers to the nature and limits of the power of society (not of politics or

government) over the individual (p.5/ Hp.1), i.e.

his concern is the tyranny of public opinion,

‘social tyranny’ or ‘tyranny of the majority’ or ‘tyranny of prevailing

feeling and opinion’ (p.8/ Hp.4). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

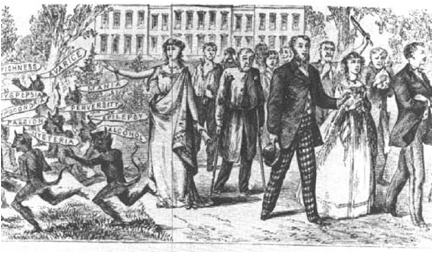

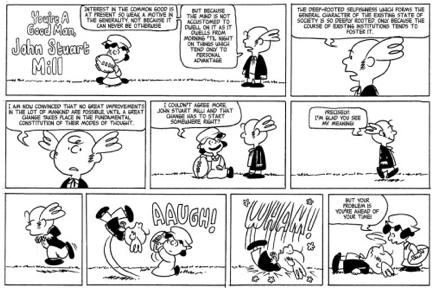

[ 3 ] In this case, to be more specific, the overwhelming

social tyranny in Victorian England

involved: |

|

–

engines of moral repression

(p.16/ Hp.13), –

false or shallow moralizing

(p.43), –

role of moral police (p.85), –

neo-Puritanism (pp.86-7). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[ 4 ] Mill’s arguments do not apply to: -

to immature human beings, e.g. children. (Hp.9) - to “barbarians” (p.13/ Hp.10), i.e.,

those still awaiting political institutional stability, -to

“backward states of society in which the race itself may be considered as in

its nonage” (p.13/ Hp.10), |

|

|

|

In

effect, in a different time or for a different society Mill might have

written a book entitled On Authority. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

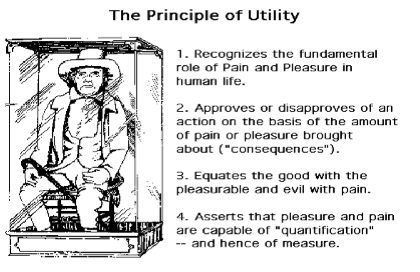

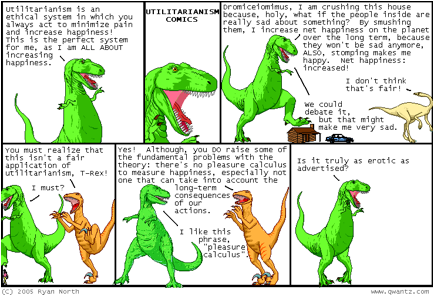

[ 5 ] Mill does NOT

appeal to abstract natural or negative right(s) but

rather to consequences or general utility in the long term, i.e.,

utilitarianism (p.14/ Hp.10); that

“Mankind are greater gainers by ...” (p.16/ Hp.12). ‘Rights’

are much too final and absolute a means of addressing the balancing act that

Mill argues is necessary over time. |

|

|

|

|

|

[ 6 ] social compulsion may be appropriate, with

due caution, to make others do “positive acts for the benefit of others”

(p.14/ Hp.10) i.e.,

according to Mill there are some socially enforceable ‘positive duties,’ or

acts that one should feel obliged to do for others. |

|

|

|

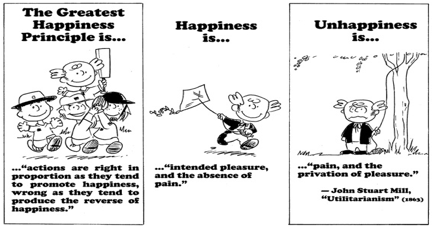

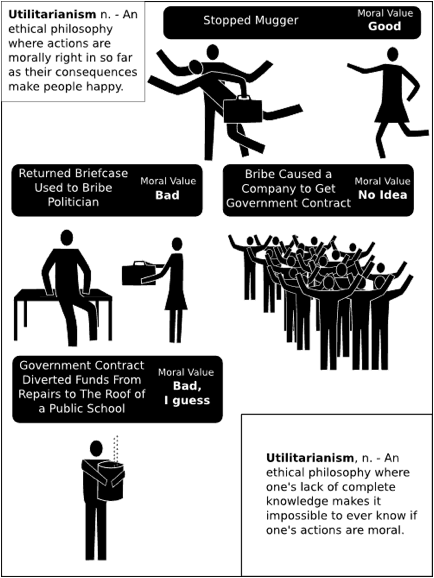

Utilitarianism -

Variant of ‘consequentialism’ -

‘greatest good of greatest

number’ -

maximize collective ‘utility’

– reduce pain, increase pleasure. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

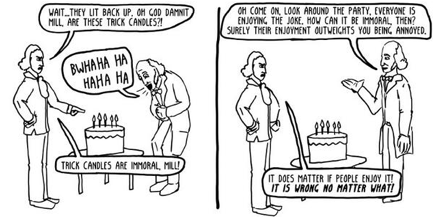

Problems with Utilitarianism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Absolutism v consequentialism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Hp16)

(Hp16)